Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital. My column in The Times this week argues that anti-vaxxers, conspiracy theorists and political zealots have tended to flourish in prosperous, rational, liberal societies which protect them from the consequences of their own actions. The irony of course is that the cranks tend to hate precisely the medical and political systems that guarantee their safety and comfort. But as society becomes more turbulent, dangerous and irrational they are more exposed to the repercussions of their own irrationality . The argument is usefully illustrated by an outbreak of measles in an area of Texas with very low vaccination rates - the state’s worst since the twentieth century.

I also appeared on The Times’s podcast The Story to talk about getting rid of my smartphone. I’m always interested in hearing from people who are contemplating doing the same. Please get in touch in the comments if you are thinking about it.

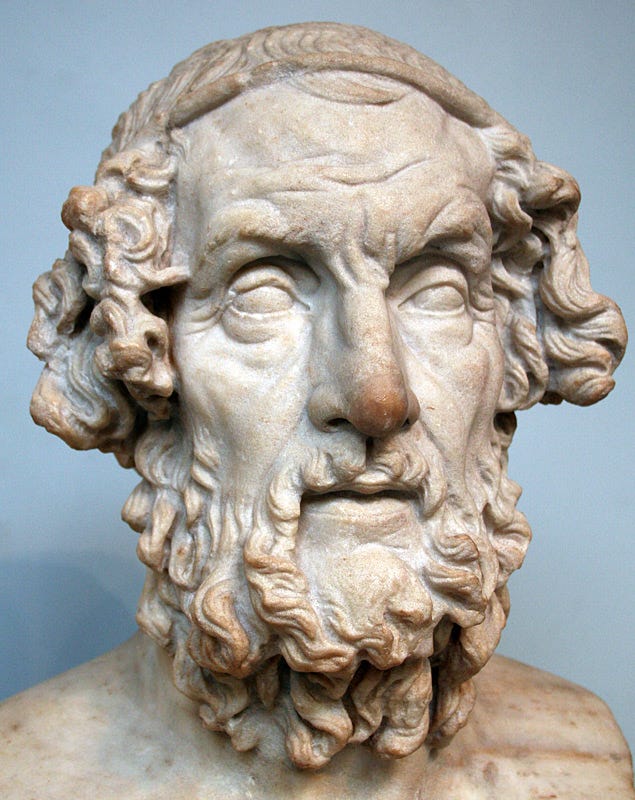

Orality and Literacy

Last week I read Walter Ong’s superb book Orality and Literacy. I can’t recommend it highly enough. It’s provoking, clearly-written and full of ideas. A genuinely exciting book to read.

I came across it via an article Ian Leslie linked to in his newsletter which argues that as the age of literacy ends, our society is beginning to demonstrate many of the characteristics of a pre-literate oral culture. Among the attributes of oral societies are an addiction to the memorable, such as formulaic and cliché language, “heavy” crudely-characterised personalities (like Cerberus or Donald Trump or Marvel superheroes) and to more violent forms of expression. This is in contrast to print which fosters subtlety, logical argument and emotional distance. It’s an attractive argument and one I’ve seen several people making. I perhaps half buy it. I certainly agree that we’re exiting the age of literacy but I’m not necessarily sure that the a return to orality is entirely the right way of framing the future we’re heading into. For instance, one of Ong’s central arguments about oral cultures is that words are highly ephemeral - but of course online all words whether written or spoken are preserved forever. Is this a second age of orality or just something . . . worse!?

Anyway, Ong’s book is extremely interesting about the way literacy changes our minds and our societies. Here are a handful of interesting bits from the book. I’ve quoted him at length because I think he is so fascinating. But it’s definitely worth getting the book because it’s virtually all this good.

If you want to retain knowledge and insights in an oral culture you must “think memorable thoughts”:

How could you ever call back to mind what you had so laboriously worked out? The only answer is: Think memorable thoughts. In a primary oral culture, to solve effectively the problem of retaining and retrieving carefully articulated thought, you have to do your thinking in mnemonic patterns, shaped for ready oral recurrence. Your thought must come into being in heavily rhythmic, balanced patterns, in repetitions or antitheses, in alliterations and assonances, in epithetic and other formulary expressions, in standard thematic settings (the assembly, the meal, the duel, the hero’s ‘helper’, and so on), in proverbs which are constantly heard by everyone so that they come to mind readily and which themselves are patterned for retention and ready recall, or in other mnemonic form. Serious thought is intertwined with memory systems. Mnemonic needs determine even syntax (Havelock 1963, pp. 87–96, 131–2, 294–6).

Protracted orally based thought, even when not in formal verse, tends to be highly rhythmic, for rhythm aids recall, even physiologically. Jousse (1978) has shown the intimate linkage between rhythmic oral patterns, the breathing process, gesture, and the bilateral symmetry of the human body in ancient Aramaic and Hellenic targums, and thus also in ancient Hebrew. Among the ancient Greeks, Hesiod, who was intermediate between oral Homeric Greece and fully developed Greek literacy, delivered quasi-philosophic material in the formulaic verse forms that structured it into the oral culture from which he had emerged

Oral societies are more politically and intellectually conservative because they have to commit huge cognitive resources to memorising and preserving information, meaning they have less energy to dedicate to analysis and innovation:

Since in a primary oral culture conceptualized knowledge that is not repeated aloud soon vanishes, oral societies must invest great energy in saying over and over again what has been learned arduously over the ages. This need establishes a highly traditionalist or conservative set of mind that with good reason inhibits intellectual experimentation. Knowledge is hard to come by and precious, and society regards highly those wise old men and women who specialize in conserving it, who know and can tell the stories of the days of old. By storing knowledge outside the mind, writing and, even more, print downgrade the figures of the wise old man and the wise old woman, repeaters of the past, in favor of younger discoverers of something new.

The spread of literacy in Greece enabled the birth of philosophy. Plus an interesting thought about why Plato excluded philosophers from the Republic which I assume must be disputable (chirographic = related to writing):

In an oral culture, knowledge, once acquired, had to be constantly repeated or it would be lost: fixed, formulaic thought patterns were essential for wisdom and effective administration. But, by Plato’s day (427?–347 BC) a change had set in: the Greeks had at long last effectively interiorized writing—something which took several centuries after the development of the Greek alphabet around 720–700 BC (Havelock 1963, p. 49, citing Rhys Carpenter). The new way to store knowledge was not in mnemonic formulas but in the written text. This freed the mind for more original, more abstract thought. Havelock shows that Plato excluded poets from his ideal republic essentially (if not quite consciously) because he found himself in a new chirographically (writing styled poetic world in which the formula or cliché, beloved of all traditional poets, was outmoded and counterproductive.

Oral cultures tend to be more verbose:

Thought requires some sort of continuity. Writing establishes in the text a ‘line’ of continuity outside the mind. If distraction confuses or obliterates from the mind the context out of which emerges the material I am now reading, the context can be retrieved by glancing back over the text selectively. Backlooping can be entirely occasional, purely ad hoc. The mind concentrates its own energies on moving ahead because what it backloops into lies quiescent outside itself, always available piecemeal on the inscribed page. In oral discourse, the situation is different. There is nothing to backloop into outside the mind, for the oral utterance has vanished as soon as it is uttered. Hence the mind must move ahead more slowly, keeping close to the focus of attention much of what it has already dealt with. Redundancy, repetition of the just said, keeps both speaker and hearer surely on the track. Since redundancy characterizes oral thought and speech, it is in a profound sense more natural to thought and speech than is sparse linearity. Sparsely linear or analytic thought and speech are artificial creations, structured by the technology of writing

[. . .]

Redundancy is also favored by the physical conditions of oral expression before a large audience, where redundancy is in fact more marked than in most face-to-face conversation. Not everyone in a large audience understands every word a speaker utters, if only because of acoustical problems. It is advantageous for the speaker to say the same thing, or equivalently the same thing, two or three times. If you miss the ‘not only…’ you can supply it by inference from the ‘but also…’. Until electronic amplification reduced acoustical problems to a minimum, public speakers as late as, for example, William Jennings Bryan (1860– 1925) continued the old redundancy in their public addresses and by force of habit let them spill over into their writing. In some kinds of acoustic surrogates for oral verbal communication, redundancy reaches fantastic dimensions, as in African drum talk. It takes on the average around eight times as many words to say something on the drums as in the spoken language (Ong 1977, p. 101). The public speaker’s need to keep going while he is running through his mind what to say next also encourages redundancy. In oral delivery, though a pause may be effective, hesitation is always disabling. Hence it is better to repeat something, artfully if possible, rather than simply to stop speaking while fishing for the next idea. Oral cultures encourage fluency, fulsomeness, volubility. Rhetoricians were to call this copia.

Oral cultures favour aggressive language because it is more memorable (agonistic = combative):

Many, if not all, oral or residually oral cultures strike literates as extraordinarily agonistic in their verbal performance and indeed in their lifestyle. Writing fosters abstractions that disengage knowledge from the arena where human beings struggle with one another. It separates the knower from the known. By keeping knowledge embedded in the human lifeworld, orality situates knowledge within a context of struggle. Proverbs and riddles are not used simply to store knowledge but to engage others in verbal and intellectual combat: utterance of one proverb or riddle challenges hearers to top it with a more apposite or a contradictory one (Abrahams 1968; 1972). Bragging about one’s own prowess and/or verbal tongue-lashings of an opponent figure regularly in encounters between characters in narrative: in the Iliad, in Beowulf, throughout medieval European romance, in The Mwindo Epic and countless other African stories (Okpewho 1979; Obiechina 1975), in the Bible, as between David and Goliath (1 Samuel 17:43–7). Standard in oral societies across the world, reciprocal name-calling has been fitted with a specific name in linguistics: flyting (or fliting).

[. . .]

Not only in the use to which knowledge is put, but also in the celebration of physical behavior, oral cultures reveal themselves as agonistically programmed. Enthusiastic description of physical violence often marks oral narrative. In the Iliad, for example, Books viii and x would at least rival the most sensational television and cinema shows today in outright violence and far surpass them in exquisitely gory detail, which can be less repulsive when described verbally than when presented visually.

Other Things

The human mind is in recession

Not to bang on about this too much but an interesting piece in the Financial Times argues that “the human mind is in recession”:

Trying to absorb too much content has negative side-effects. “Constant exposure to information and notifications can overwhelm our cognitive capacities,” said Mithu Storoni, author of Hyperefficient, a book about optimising our brains. “Flitting between stimuli reduces our attention span, and the overload can contribute to mental fatigue, impaired memory and increased stress.” Indeed, there is a relationship between overload and brain health. High social media usage has been associated with higher levels of depression, particularly in younger cohorts. High screen time can also worsen symptoms of ADHD, and has been linked to a higher risk of dementia.

Robert Hughes on Julian Schnabel

Still enjoying reading old Robert Hughes pieces. His take-down of the artist Julian Schnabel and the shallow collectors who indulged him is one for the ages:

Most of the aspiring collectors, some of whom would duly end up on museum boards, or even with their own private museums, could not have told you the difference between a Cezanne watercolor and a drawing by Parmigianino. Their historical memory went back as far as early Warhol, where it tended to stop. Their sense of the long continuities of art was, to put it tactfully, attenuated. Insofar as they thought about the matter, they were apt to see 20th-century art history as a series of neatly packaged attacks launched at the frowning ramparts of “tradition”—first the Fauves, then the Cubists, then the Expressionists, then the Constructivists, and so on, to Abstract Expressionism and Pop. This reflex, applied to the present, meant they all bought essentially the same painting by the same artists—a herd instinct that explains the monotony to which one is condemned when passing from one new collection in Beverly Hills to the next.

Terrifying Geopolitics

Particularly good episode of Helen Thompson and Tom McTague’s podcast These Times about how/if Europe will cope without America. They know all kinds of stuff that nobody else does about how Chinese goods get transported through Belarus and so on.

Babble Machines

Came across this fun/prophetic paragraph rereading John Carey’s great book The Intellectuals and the Masses:

In [HG Wells’s] novel of 1899, When the Sleeper Wakes, a character called Graham comes out of a cataleptic trance to find himself 203 years in the future. London has by this time become a huge glass-roofed conglomeration of innumerable levels – ‘a gigantic glass hive’ – with a population of 33 million. Down in the subterranean levels of the city live the pale, toiling masses (‘Masses – the word comes from your days – you know, of course, that we still have masses,’ a guide explains to Graham). This submerged population talk in a crude dialect and listen to ‘Babble Machines’ (the replacement for newspapers), which broadcast crude, false news items and shout slogans – ‘Blood! Blood!’ or ‘Yah!’ – to attract attention. Even in the upper city levels, Graham finds, there are no books any more, only videos or porn-videos, labelled in simple phonetic English.

Eric Hobsbawm

After listening to Alex Ross’s Wagnerism I have undergone something of a personal revolution and become open to the idea of audiobooks. I’ve been enjoying listening to Eric Hobsbawm’s The Age of Capital. It’s a bit like a very long episode of the Rest is History but with more Marxism and no jokes. I’m not sure I’ll necessarily finish it as we’re getting very bogged down in statistics about industrial production in mid nineteenth century Prussia and so on but if that’s your thing you’ll certainly enjoy it. There’s something quite peaceful about walking around London with someone monotonously intoning, “In Belgium, 3,000 miles of telegraph cable were laid, in France 7,000 miles of telegraph cable were laid, in Britain 17,000 miles of telegraph cable were laid, in Prussia, 14,000 miles of telegraph cable were laid…” (invented this quote but it is not untrue to the spirit of the book).

Poem of the Week: Coming by Philip Larkin

In celebration of (slightly) warmer weather, one of my very favourite Larkin poems about the feeling that “it will be spring soon”. So many superbly delicate touches here. “Foreheads of houses” is brilliant. A lesser poet could easily have said “faces” and missed the crucial note of impassivity. “Deep bare garden” is great - you know exactly the kind of overgrown, leafless February garden he means. The thrush’s “fresh-peeled” voice is maybe a touch too self-consciously poetic for the atmosphere of the poem. And the last lines are stunning:

It will be spring soon—

And I, whose childhood

Is a forgotten boredom,

Feel like a child

Who comes on a scene

Of adult reconciling,

And can understand nothing

But the unusual laughter,

And starts to be happy.

Full poem here.

My smart phone story. When I was writing a book recently, I managed (to my surprise) to be disciplined about phone and social media use. No distractions while I concentrated on the book, for about a year and a half. Then, when it was all done, I went back to my old ways; head down, scrolling, posting, checking. Almost immediately, my brain had what felt like a spasm. My concentration and memory went haywire. I felt depressed. I forgot things all the time. Did daft things like drive off without paying for petrol. The worst passed after a few months, and it may have been a more straightforward reaction to stopping concentrating on that one thing, the book. But it felt to me like my brain crunching the gears as it rewired itself to short-term thinking, seeing the world in 240 characters rather than paragraphs, and a bombardment of images and videos. I still feel like I’m at about 80% of where I was, mid-book. Please keep up your campaign, so important!

Great article -- I too am a very big fan of Ong's Orality and Literacy.

Ted Chiang has a great short story that fictionalizes Ong's story about Tiv genealogies ("The Truth of Fact, The Truth of Feeling") and combines it with a futuristic story about being able to accurately record all our life events. Really well done.

Also, have you come across The Gutenberg Parenthesis by Jeff Jarvis? This is about the ideas developed by Lars Ole Sauerberg and Tom Pettitt of the University of Southern Denmark. The Gutenberg parenthesis represents the five hundred years between the invention of the printing press and the rise of the internet, in which the printed word and the bound text dominated human culture in the West.

Their idea is that this period is just a short-term blip in how humans communicate and exchange ideas. With the invention of the internet, we are now engaged in various forms of electronic, digitally mediated communication, which moves society away from static, stable, closed texts, which are the property of a single author, toward a form of secondary orality, with texts that are more fluid, less stable, and reflect the input of multiple individuals. Tom Pettitt says "if one wishes to know how we will communicate in the future, the answer seems to be: like a medieval peasant"

There's a good talk by him here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O-zzkgsKOBk&ab_channel=MITComparativeMediaStudies%2FWriting