Declining fertility optimism, architecture is getting better, the politicisation of the humanities, the prophecies of Walter Ong

Plus more links and quotes

Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital!

In The Times this week I wrote about the crisis of universities and wondered whether we will one day look back on the phenomenon of mass higher education as a post war blip.

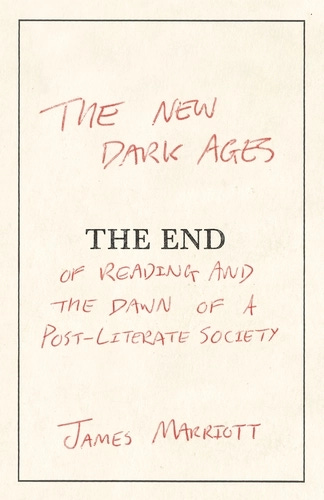

Excitingly, my book has a cover. I’m highly biased (I consider The New Dark Ages essentially my first born child) but I think this is genius:

Somehow the fact you can now order the book on Amazon makes it seem more real. I have discovered the diverting past time of checking my ranking in the various eccentric categories Amazon comes up with for books. Earlier this week I got up to 17th place in “Reading Skills Reference”.

Don’t sweat declining fertility

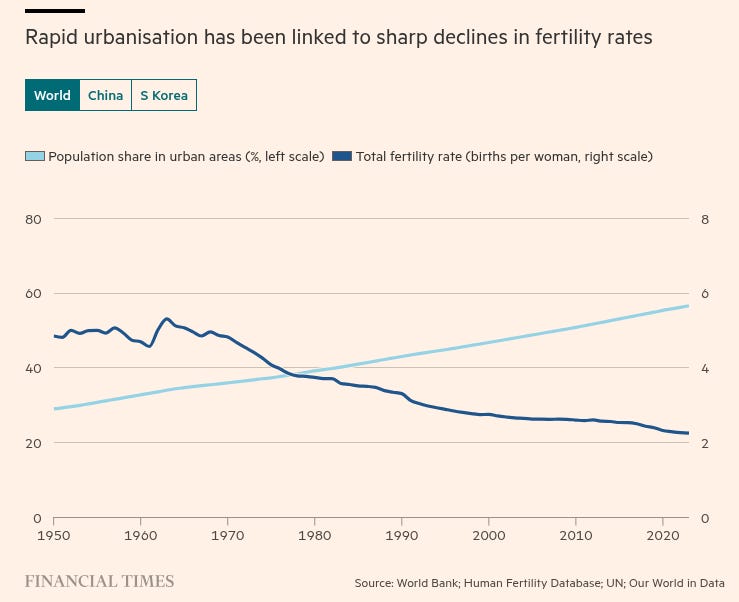

In the Financial Times Martin Wolf writes very interestingly on declining fertility. Two of the major drivers are urbanisation and education:

The former moves people to places where land is relatively expensive. The latter transforms children from productive assets in the quite short term into costly long-term investments. Grown children may also now move far away from their parents. Modernity also creates capital markets, pensions and welfare states, all of which are a substitute for children’s financial support. Finally, it creates new pleasures, which compete with those of having children.

Interestingly, Wolf argues that we are over-worrying about declining fertility. I think this is an interesting point:

A favourite argument why the declining fertility rates are potentially catastrophic is that “dependency ratios” will soar. Measured in the normal way, as ratios of people over 65 to those aged 15-64, this is true. But this ignores the fall in the proportion of the young, many of whom are now dependent until their twenties. Overall dependency ratios will rise far less, except in the more extreme cases of low fertility. It also ignores the potential for people to work longer. In South Korea, 38 per cent of people over 65 were working in 2024, against a ludicrous 4 per cent in France.

Why are people in English-speaking countries dying early?

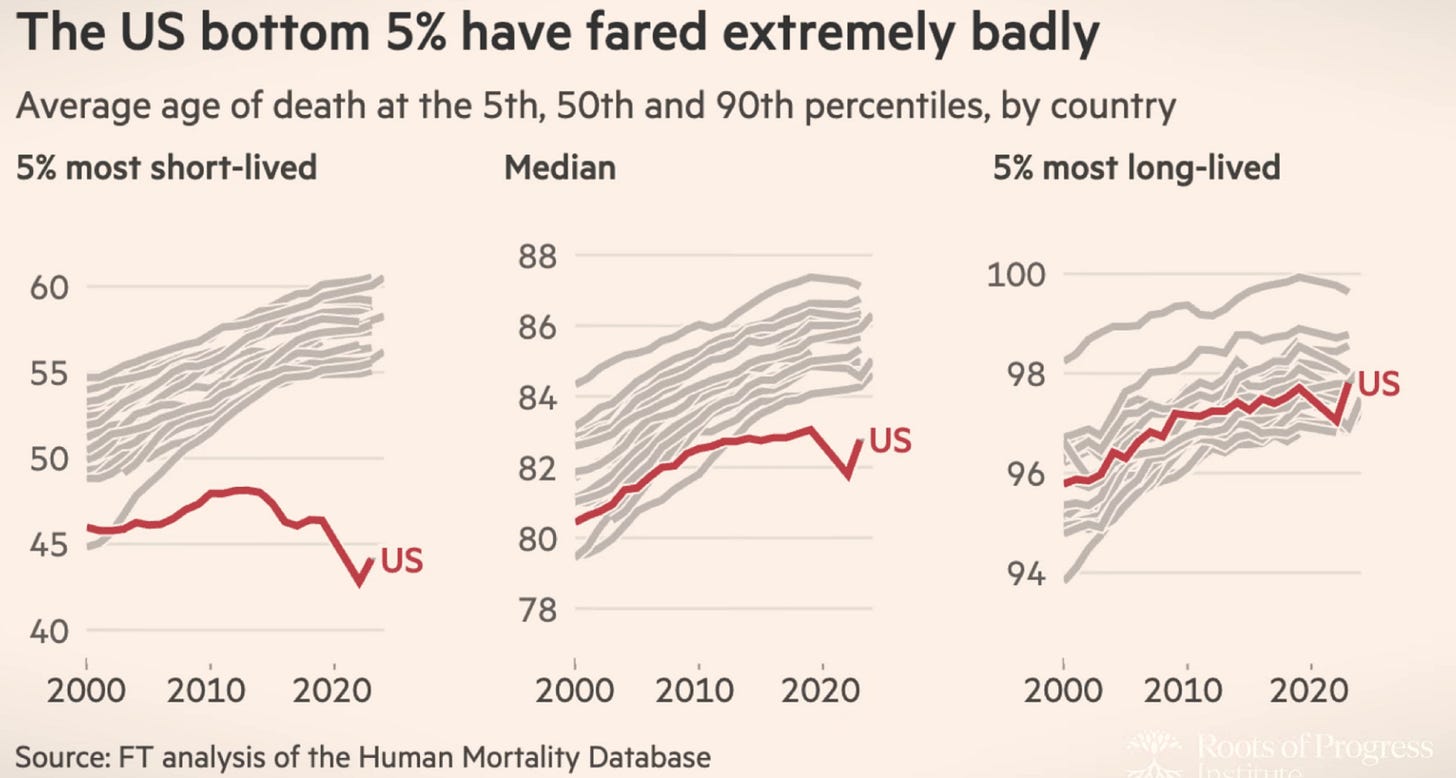

This is a fascinating talk by the Financial Times’s great John Burn Murdoch about why life expectancy has stalled in English-speaking countries. There is no great change among those living average and long lives. But there has been a significant drop among the shorter-lived part of the population.

Those at the bottom are doing much worse:

A lot of this seems to be to do with unemployment and what are traditionally called “deaths of despair”— to do with a sense of purposelessness and ensuing drug addiction, alcoholism and suicide. As Burn Murdoch rather hauntingly points out this has alarming implications for the potential coming wave of AI unemployment.

And he also interestingly points out that that “deaths of despair” is too broad a diagnosis and the main problem seems to be increasing social isolation.

You can watch the rest of the video here:

The politicisation of the humanities

This is a long investigation from the Atlantic into how America’s biggest and most powerful academic funding body for the humanities, the Mellon Foundation, pushed to politicise the humanities, turning them into essentially a branch of social justice studies. In a way it’s all fairly unsurprising. Lots of conferences asking things like, “How do the humanities contribute to anti-oppressive work, and how can humanities methods—from inquiry and critique to creative production and performance—dismantle systems of oppression, create and sustain community and solidarity, and advance liberation?”

For those of us for whom politics is about the least interesting things about art and literature this is all bleak:

Some of Mellon’s recent grants have the potential to remake liberal-arts education entirely. The foundation’s Humanities for All Times project, launched in 2021, is premised on the notion that “today’s humanities undergrads are tomorrow’s social justice leaders.” Over the past several years, the foundation has regularly invited small cohorts of liberal-arts colleges to apply for grants—up to $1.5 million each—that support social-justice-aligned curricular development. The application guidelines note that “submissions oriented toward revising an institution’s entire general education program are especially welcome.” That is to say, college administrators and academics are encouraged to submit proposals for projects that would overhaul their core requirements for all students, in every major, in the service of a progressive political program.

Acquaintances in British academia report a similar vibe. A lecturer friend once sent me this from a conference about “recentering trees” as “active, cognisant and intentional beings” in their own right:

We will approach trees as trees - both as individuals and as collectives, prioritising their perspectives and arboreality within their distinct ecosystems and environments. Moving beyond previous work that has situated trees within human narratives, this conference will attempt to consider ‘tree-ish’ thinking within a broad range of subjects, from the Humanities to the Social and Natural Sciences. Taking this perspective will allow us to examine how trees, across space and time, have engaged with and formed networks alongside humans and nonhuman others.

[…] Our conference will explore the idea that trees and other nonhumans are active, cognisant, and intentional beings- an awareness that has all too often been lost.

This is not actually made up.

Dominic Sandbrook

I loved this profile of Dominic Sandbrook by Tanjil Rashid in the New Statesman. It’s very interesting and astute about where Sandbrook sits in the tradition of English public intellectuals.

I especially liked this observation: “The celebrity historian is the genre of public intellectual Britain has traded in most – as profitably as France has done in philosophers, Germany in social scientists, and Russia in ideologically deranged novelists.”

The possibility of a Dominic Sandbrook and John Carey-hosted podcast on Call of Duty is one of the great what-ifs of entertainment history:

Sandbrook’s populist tendency places him in a robust critical tradition of which he is more conscious than he lets on. He unpretentiously claims not to read literary criticism (“I read a lot of French literary criticism in the Nineties… that buys you a lot of credit for the rest of your life.”) Yet the writer he returns to dozens of times in our conversation is not a historian or novelist but a literary critic, John Carey; he describes the legendary book reviewer as his “absolute hero”, because he “had the democratic, open-minded spirit you should have as a critic”.

Sandbrook recalls how when his wife went to get, as a gift, a signed copy of Carey’s biography of William Golding, they ended up having a conversation not about the novelist but Call of Duty; the Merton professor of English literature at Oxford was apparently seized by a desire to know what Sandbrook had made of it. “That was all he wanted to talk about.”

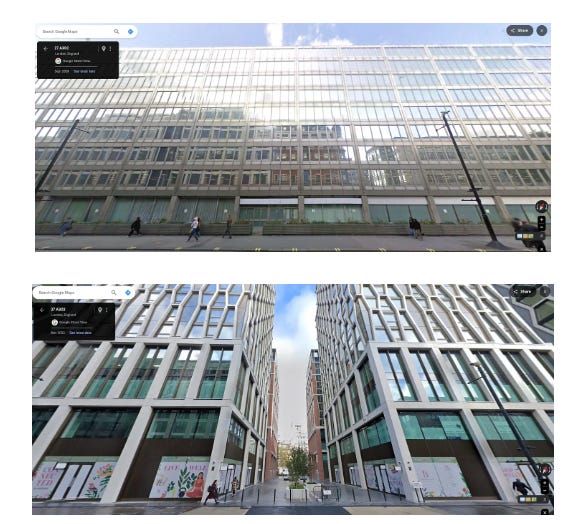

A walk down a London street

A couple of weeks ago I linked to Samuel Hughes’s piece about Victorian cities. Here is another charming piece by him about the architectural history of a single street, in this instance Victoria Street in central London. “Much of it is very ugly” he writes. But his encouraging conclusion is that British architecture is getting better:

What have we learnt on our walk? The standard narrative that British architecture had a precipitous visual decline in the twentieth century is, as usual, vindicated. But we have also seen signs of recovery. The architecture of the last ten years shows inconsistent but sometimes striking improvement in respect of planning and massing, and some more tentative improvement in respect of materials and detailing. Perhaps we may live to see someone try a five-part composition.

One instance he cites is the redevelopment of The Broadway:

It is easy to be snide about The Broadway, but actually it is a great improvement on its unrelentingly grim predecessor… It has broken down the relentless horizontality of the building it replaced, and whatever the defects of the new facades, they are better structured and more lively than those of their predecessor. If all English architecture was improving at this rate, we would have much to look forward to.

I know nothing about architecture but I’m inclined to agree. Near me in East London there are a lot of identikit fake warehouses being built. They rarely strike me as original but at least they’re not oppressive in the way sixties tower blocks are. Things seem to be moving in an airier and rather less grim direction.

AI writes romance

An interesting piece from the New York Times about the large number of romance novels that are being written by AI: “Future Fiction Press, a new publishing company produces A.I.-generated novels. So far, the press has released 19 romance novels that have been downloaded 20,000 times”.

Already productive romance novelists are working much faster:

Ms. Hart was always a fast writer. Working on her own, she released 10 to 12 books a year under five pen names, on top of ghostwriting. But with the help of A.I., Ms. Hart can publish books at an astonishing rate. Last year, she produced more than 200 romance novels in a range of subgenres, from dark mafia romances to sweet teen stories, and self-published them on Amazon. None were huge blockbusters, but collectively, they sold around 50,000 copies, earning Ms. Hart six figures.

For some reason people don’t talk about the threat AI poses to writers as much as they once did. I think AI writing has improved immensely in the last few months. In many cases (and prompted properly) it’s very hard to tell from human work.

In a depressing recent Economist podcast, a journalist asks his colleagues whether they can distinguish by his column and one written by an AI and … they can’t really say which is which.

The prophetic genius of Walter Ong

This is a good conversation between Derek Thompson and Joe Wiesenthal about Walter Ong, the great theorist of oral and literate cultures. Ong’s book Orality and Literacy is becoming more and more widely acknowledged as one of the prophetic books of the twentieth century (the best introduction to Ong’s ideas is this Ian Leslie article).

Thompson and Wiesenthal are interesting on the question of whether AI is an “oral” or a “literate” technology. Thompson says:

This is a quote from Orality and Literacy by Walter Ong:

A written text is basically unresponsive. If you ask a person to explain his or her statement, you can get an explanation. If you ask a text, you get back nothing, except the same often stupid words, which called for your question in the first place.

I remember rereading that section on a plane recently and I jolted up in my seat. I was like, that’s what AI has changed. You can enter into conversations with text. That is true either at a literal level—like I can download a PDF of a book, and give it to Claude and be like, Claude, can we talk about this book? But also, at a higher abstract level, we’re talking about a technology that is pre-trained on text. It’s pre-trained on literacy. But we have an oral, which is to say conversational, relationship with that training corpus. It’s weird.

Finally…

I’m reading Samuel Johnson’s short novel Rasselas — reportedly written in a week to pay for his mother’s funeral. It’s wonderful. I especially loved this:

Being now resolved to be a poet, I saw every thing with a new purpose; my sphere of attention was suddenly magnified: no kind of knowledge was to be overlooked. I ranged mountains and desarts for images and resemblances, and pictured upon my mind every tree of the forest and flower of the valley. I observed with equal care the crags of the rock and the pinnacles of the palace. Sometimes I wandered along the mazes of the rivulet, and sometimes watched the changes of the summer clouds. To a poet nothing can be useless.”

As always, let me know what books you’re reading, podcasts you’re listening to etc.

Until next week,

James

Whilst the text about the tree conference is truly awful and makes your skin crawl there is something in the sentiment that should not be dismissed. You could completely rewrite it as a ecologist who has studied forests for years as something like

"Fifty years of field work has made one thing undeniable to me: forests are not a backdrop to life, they are a form of it — networked, responsive, and ancient beyond our intuition. We now have the data to show what indigenous peoples have always known. A tree is not a post with leaves. It communicates, it allocates resources to kin, it responds to threat. The tragedy is not that we are only now discovering this. The tragedy is what we destroyed while we were busy not paying attention."

Am feeling more and more ambiguous about AI. I use it at work to complete dull tasks and as a sanity check - updating policy documents, ensuring that my correspondence is GDPR compliant and bland even if I myself am feeling less than diplomatic. But I resent its impact and see dangers for my own children and all the students in schools around the world whose lives may be drained of meaning and validity by greedy corporations preferring to use machines over humans for so many tasks. I loathe the arrogance and entitlement of the developers building their ravenous data centres and unleashing this technology on us with no meaningful regulatory framework. The way it is emerging in our world seems more redolent than ever of the fundamental contempt that the rich seem to have for anyone who does not wish to play the materialist game of growth at all costs, gain at all costs.

Apart from that, I want to say a big thank you to you and Ian Leslie - I’ve just finished reading Proust and the Squid and am heading towards Walter Ong, who somehow never crossed my horizons before.