How to spot AI writing, the death of zombie art, the first tech bubble, out of touch politicians and RIP Tony Harrison

Plus more links and quotes

Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital! This week in my column in The Times I argued that smartphones must not be allowed to become compulsory in society. Increasingly you need a smartphone to bank, to buy parking tickets, to take the train. A friend has to use his smartphone to get into his office. There must always be an option to opt out of the tech-addicted society.

Excitingly, Cultural Capital was recommended on Marina Hyde and Richard Osman’s excellent podcast The Rest is Entertainment this week.

The birth pangs of print

The writer

In time the technology then finds realistic use-cases and gradually surges back, often taking advantage of all the infrastructure that was built in the first phase of wild over-enthusiasm. Thompson believes something like this may be true of AI.

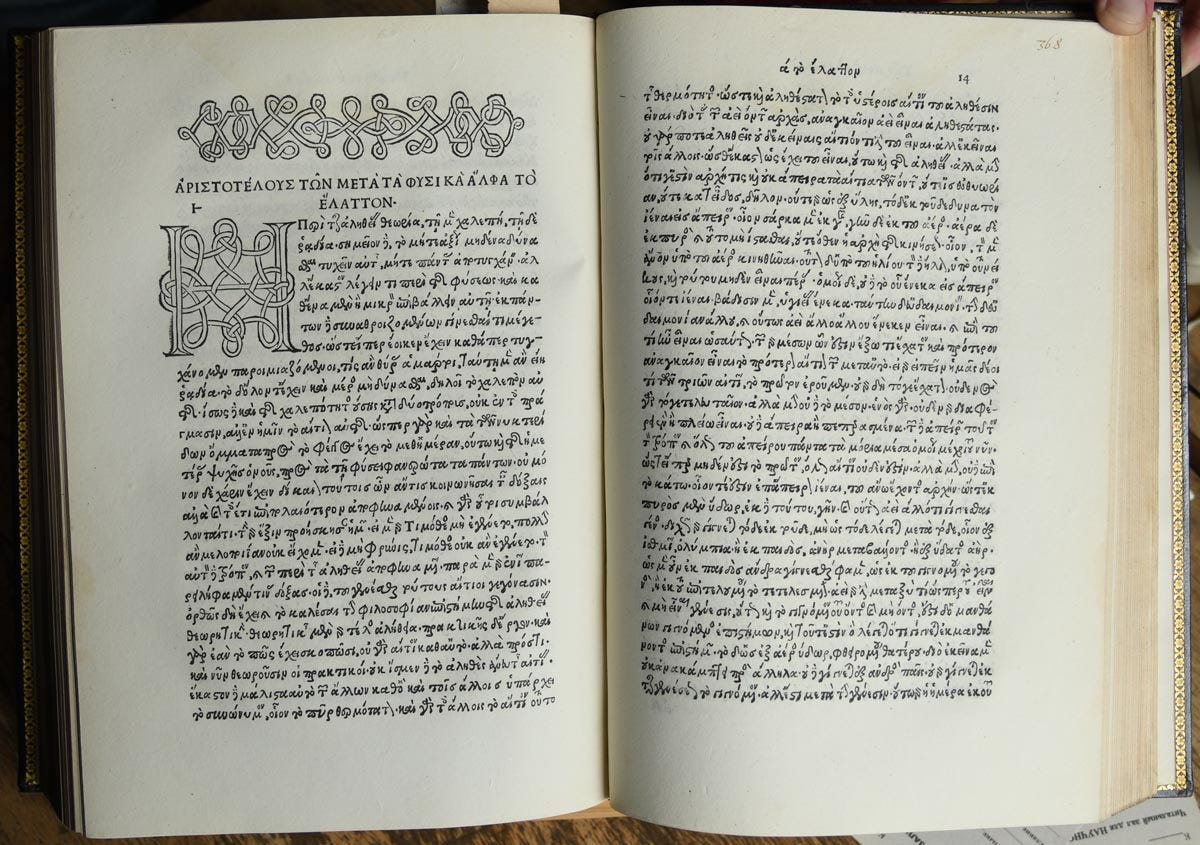

Interestingly, according to Andrew Pettegree’s fascinating history of the early years of print, The Book in the Renaissance (highly recommended), the invention of the printed book followed the same trajectory. Was print the first tech bubble?

The parallels are really remarkable. It began with excitement:

Print spread like wildfire, fuelled by the enthusiasm of a sophisticated urban market. But this enthusiasm was based more on fascination with the new technology than on rational calculation. It was still far from clear whether Italy’s community of readers could deal with so large a large a volume of printed books.

Then came the crash:

The first crisis of production hit Venice in 1473, immediately following the extremely rapid take-off period. Production fell to half the peak of 1471–72, and eight of the dozen printers working in the city were driven from the market.

The problem was (as with many new technologies) that the market hadn’t yet been created. Customers had to be trained for print. You need widespread education to create a mass audience for books.

In particular the market was glutted with editions of classical texts, including multiple editions of works for which there were simply, as yet, insufficient readers.

Pettegree also says that consumers had to be re-trained out of manuscript-era buying habits. Most people were used to the idea that if you wanted a book you first had to know what book it was you wanted. Then you had to commission that book to be written out for you by a local scribe. The idea you might browse a bookshop and end up purchasing a book you never knew you wanted, or perhaps had never even heard of, was quite alien.

There were also complaints about quality. Many printed books looked terribly shoddy compared to manuscripts:

The first printed books could not live up to the standard set by manuscript production in Italy. They were often dirty, smudged and inaccurate. They included too many mistakes. The inefficiency and carelessness of printers would be a repeated lament of authors throughout the era of hand-press printing, but in this first generation it had a philosophical edge: the charge that print had debased the book.

Eventually people learned to deal with less beautiful books and came to love access to myriad cheap texts. I pessimistically wonder whether we might one day look back at the arrival of AI content in this way. Those of us raised in the age of beautiful hand-made texts and images find the machine-generated “slop” alternatives intolerably ugly and shoddy. But perhaps generations after us won’t mind about the carelessness and inaccuracies.

Not all early printed books were bad, of course. I love the beautiful clean printing of Aldus Manutius in Venice — the famous Aldine editions. Back in my antiquarian bookselling days I was lucky to handle a couple of these:

Post-literate society latest

The great

My favourite art podcast returns

Waldy and Bendy’s Adventures in Art was one of my favourite podcasts when it launched in the pandemic. The art critic Waldemar Janusczak and the art historian Bendor Grosvenor are The Rest is History of art. They stopped the podcast a couple of years ago. I’d really missed it. I’m so glad it’s back. It’s so funny, opinionated, informative and full of life. A genuine must listen.

I reviewed it in The Times here.

Is the art bubble popping?

Speaking of bubbles… For decades, art has been used as an investment. But as Janusczak points out on the podcast, the bubble finally seems to be bursting. “That time when art was a way of piling up lots of cash seems to be ebbing away”, he says. Nowadays, “contemporary art is moaning and groaning about losing sales”. Prices are falling even as other investments like gold, shares and bitcoin have all gone up.

It seems the next generation of millionaires is just not into art the way their parents were. They spend more time online and are interested “things that play well on the world wide web”.

This interesting piece in the Art Newspaper argues that genuine masterpieces will survive but the kind of “zombie art” mass-produced as an asset for investors is doomed:

The “artberg” of ultra-expensive Modern and classic contemporary works accumulated over the years by boomer collectors does not appeal to younger generations. Only masterpieces will sell well. The speculative and financialised side of the market “is going and will go more because few can deny the opacity and lack of liquidity of art, making it improper as a financial asset”, adds Servais, who thinks prices are too high because the “infrastructure of the current market is too expensive”. The market for “real” art—rather than the undemanding “zombie” art produced for fairs—is the “only sustainable way forward”, Servais says.

How politicians are out of touch with voters

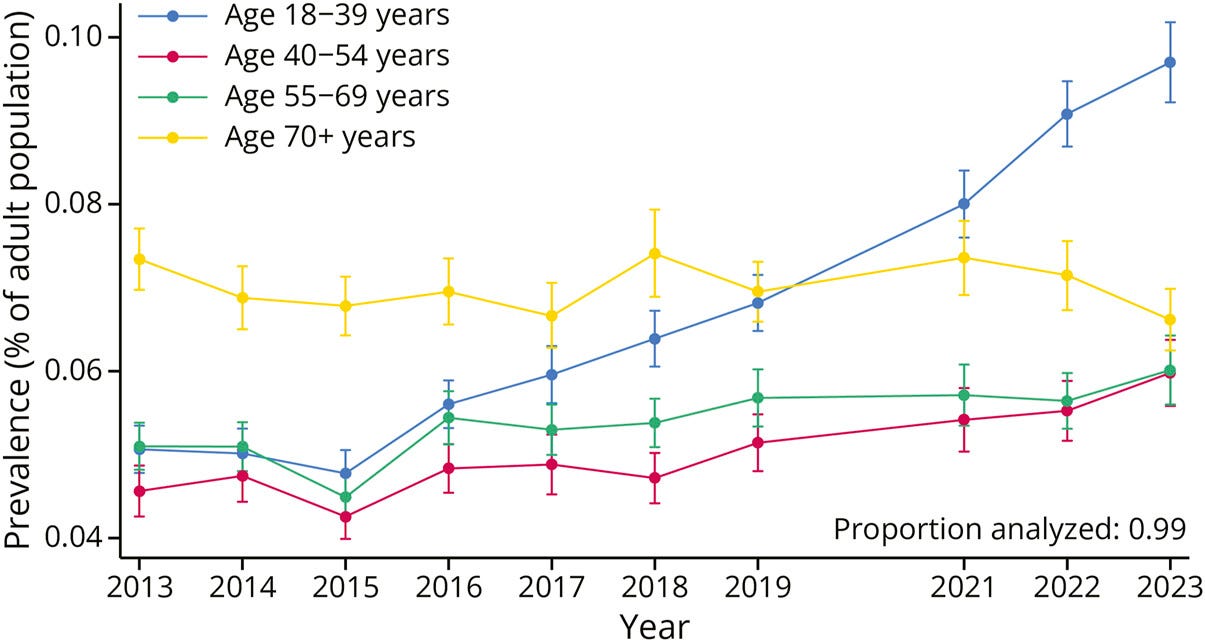

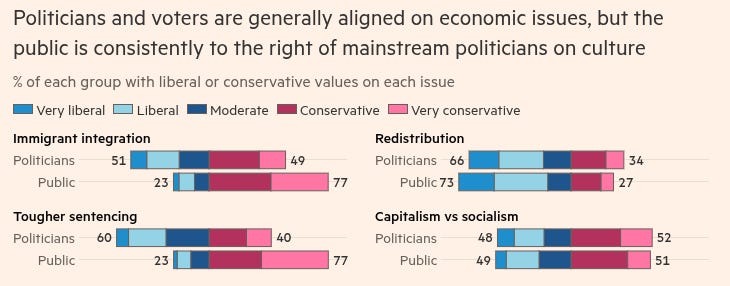

Here is yet another (!) fascinating piece by John Burn Murdoch in the FT exploring how voters and politicians are mismatched on political issues. He finds that the political class and the population are on the same page on economic issues but there is a significant disparity in their attitudes to cultural issues like immigration:

[This] analysis shows that voters and mainstream politicians have long been broadly aligned on economic issues like tax and spend or public ownership. But on sociocultural issues such as immigration and criminal justice there is a yawning gulf. Western publics have long desired greater emphasis on order, control and cultural integration. Their politicians have tilted in the opposite direction, favouring more inclusive and permissive approaches.

As Burn Murdoch suggests this misalignment in values between elites and the public is probably a major factor in the rise of populism.

How to spot AI writing

I like to think I’m pretty good at spotting AI writing (being on Substack is good training as its everywhere here, usually going viral). But Naomi Alderman is the AI-spotting pro. This is her guide. I love the way she niggles away at the AI-generated phrase “steady progress, kind pacing” as almost precisely the kind of thing a human would never write:

the longer you look at it the less it means. That is the ‘word salad’ feeling. ‘nothing more to say, no more ace to play’ is human-written and the more you think about it the more heartbreaking it is. it has the quality of a person losing coherence because of emotion. ‘Steady progress, kind pacing’... what does it actually *mean*? It has a smooth ungrippable quality.

Your funny conversations aren’t actually funny

Here’s a great nugget from Steven Pinker’s fascinating new book, When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows...

As Pinker writes, there is a long abstruse and not very amusing history of academics trying to explain why jokes are funny. Recently researchers have begun to look into what makes people laugh in actual conversation. Intriguingly, it turns out in real conversation we rarely laugh at jokes. What actually makes us laugh is hardly funny at all. What causes laughter, Pinker writes, “are comments on minor indignities, incongruities, or interruptions of everyday decorum”. A lot of laughter seems to come from puncturing the status claims of other people.

Typical laugh lines in real life are “Are you sure?” “What is that supposed to mean?!” and “It was nice meeting you too!” Fewer than a fifth of the comments provoking a laugh in Provine’s sample were remotely humorous. He writes:

“Even our ‘greatest hits,’ the funniest of the twelve hundred pre-laugh comments, were not necessarily howlers: ‘You don’t have to drink, just buy us drinks,’ ‘She’s got a sex disorder—she doesn’t like sex,’ and ‘Do you date within your species?’”

As Pinker says, “your life is filled with a laugh track to what must be the world’s worst situation comedy.” He suggests, “the next time you’re in a social gathering, pay attention to the triggers of laughter. You’ll be surprised by their witlessness”.

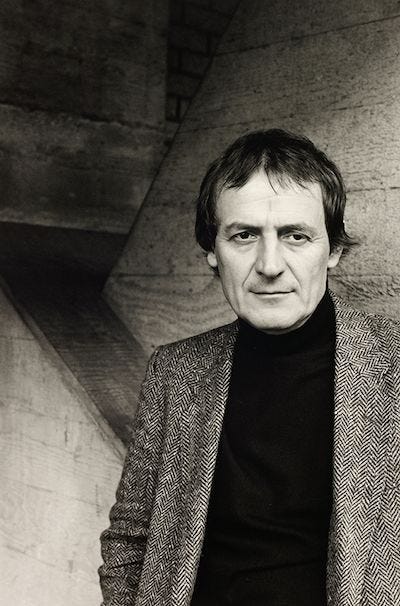

RIP Tony Harrison

The poet Tony Harrison died last week. For my money he was probably the greatest living English poet (most famously, he was the first person to say the ‘c’ word on UK television). I loved his writing.

I don’t spend a lot of time reading anti-war poetry but Harrison’s his long anti-Gulf war poem A Cold Coming was one of the first poems that ever transfixed me. I must have been about twelve when I read it. The poem’s inspiration was the famous photograph of the remains of an Iraqi soldier burned alive by an American missile. It gained new currency around the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

My dad had a copy of the poem with the gruesome photograph on the cover which horrified me and fascinated me. The poem begins:

I saw the charred Iraqi lean

towards me from bomb-blasted screen,

his windscreen wiper like a pen

ready to write down thoughts for men

I’d never heard anything like it. I learned bits off by heart which I can still recite. Rereading it now, it strikes me there was something a bit eighteenth century, a bit Swiftian, about Harrison. He liked aabb rhyme schemes, classical allusions, obscenity, bitter wit, and he wrote furiously and scurrilously on public and political affairs.

My favourite of his poems is probably ‘Initial Illumination’, another furious and inspired anti-war tirade that is also about the Lindisfarne Gospels (it works). If you click the link here you can hear Harrison reading it in his wonderful rich Leeds accent.

His most popular poems are the tender ones he wrote about the deaths of his working class parents. My favourite of these is ‘Marked with D’ (to read it, it helps to know that Harrison’s father was a baker and barely literate).

Since Harrison’s death the poem of his I’ve most loved re-reading is A Kumquat for John Keats, a melancholy and mysterious poem about getting older and death:

Then it’s the kumquat fruit expresses best

how days have darkness round them like a rind,

life has a skin of death that keeps its zest.

I love your substack posts and your Times column (the only writer left on that publication I can still read tbh) and I’m so grateful for all you’ve been sharing about the peerless Tony Harrison. I got to know him a little during his NT days, he was very thick with Harrison Birtwistle, my boss there. Unforgettable poet and tetchy human being. What an honour.

Thank you for this wonderful post James! I've just started Pinker's latest and am enjoying it! You really make me feel as if I'm part of the zeitgeist as I also picked up on Naomi Alderman's insight into AI 'writing'! Thanks for the recommendation of the Art podcast, that really appeals to me and also thanks for introducing me to Tony Harrison whom I haven't really read...but shall read now...