Notes on genius, the new dark ages, the 2008 theory of everything, Baby Grumpling, the stupidogenic society

Plus more interesting links and quotes

Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital. This week in The Times I wrote about “the politicisation of everything”. Increasingly we seem incapable of discussing any aspect of our culture — TV, adverts, brands, books, films — through anything other than a political lens. It’s getting very boring. But I also think it’s dangerous. The ambient political temperature is very high and we increasingly lack refuges from politics where people can cool off.

I also appeared on the Unherd podcast to talk about the severe recent declines in reading and the advent of the post-literate society. As literacy declines and students lose the ability to read books, I argue that we risk breaking the long chain of human knowledge that has been passed on for centuries and heading into “a new dark ages”:

***ANNOUNCEMENT: I’m off on holiday on Sunday so Cultural Capital will be running a reduced service. The newsletter will return as normal on the 19th September. ***

A few notes on musical genius

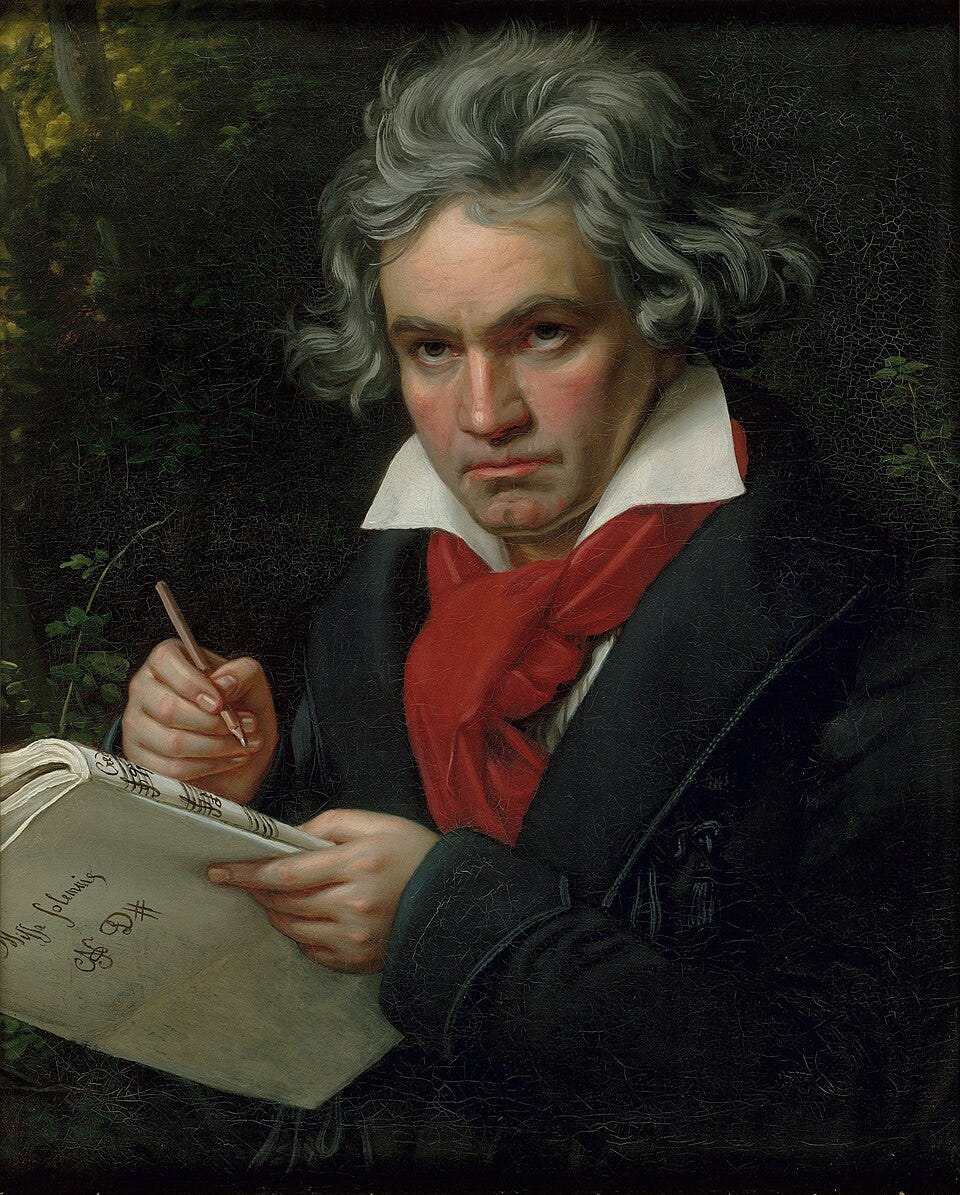

I’ve been enjoying Jan Swafford’s Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, a brilliantly readable biography of the composer. I’ve read so much literary biography so it’s fascinating to read about the early career of a genius musician. It gives you a very different perspective on how talent works. A few impressionistic thoughts:

Where literary geniuses in the romantic era often had to struggle to get established, musical geniuses like Beethoven had a much quicker route to fame (if they were talented enough to take it). A great musician can give immediate pleasure to a lot of people and can easily monetise his or her talent. In late eighteenth century Vienna, lots of people loved listening to great piano virtuosos. Piano “duels” were even organised between the hottest new soloists: one event featured a face off between Vienna’s greatest female pianists and then the city’s greatest male pianists. Then as now, people generally weren’t packing out concert halls to listen to new poets recite their work.

Musical geniuses were much more plugged into the wealthy aristocratic world of court culture. Many aristocrats loved music and respected musicians. Every other page of Swafford’s book contains a sentence like, “the king himself was a cello player”. By his early twenties Beethoven already “looked at the aristocracy not just as his equals but also as his patrons and his natural milieu”. At that stage in their careers many poets are still starving in their garrets.

The enthusiasm of aristocrats was financially useful. German princes seemed quite keen to hand the young Beethoven (and his talented contemporaries) rare trinkets and gifts of money. In his twenties Beethoven received valuable clocks, snuff boxes and even a race horse (which he barely used). By this stage in history literary geniuses were increasingly relying less on patrons and more on the cruel and capricious literary market.

It helps that music is less political. Poets who aspired to push the boundaries of their form — especially in the revolutionary romantic era — could easily find themselves giving offence to the wealthy and powerful. It’s much harder to find political objections to instrumental music. Swafford suggests that the rich musical culture of late eighteenth century Austria partly stemmed from the oppressive political environment: “Try as they might, the police could find no grounds to censor instrumental music, which had always been the city’s chief glory. In the end, symphonies, string quartets, piano concertos, and the like became virtually the only kind of free speech left in Austria”. Even so, the reactionary Austrian emperor Francis II once remarked of Beethoven “There is something revolutionary in that music!”

Musical genius requires a lot of work to acquire and is therefore more collaborative. Whereas literary geniuses learn their craft from reading books alone, musical genius requires gruelling training. For this reason, several of the famous musical names of the past worked quite closely together. When he was a young man Beethoven met Mozart and studied with a number of famous composers like Haydn and Salieri (of Amadeus fame). Indeed, Beethoven was still submitting himself to instruction in techniques like counterpoint or writing for the opera even after he had begun to compose some of his great early works. In literary history you never find e.g. Wordsworth helping the young Tennyson to improve his scansion.

In spite of this Beethoven looked up to poets as superior to musicians: “in his scale of values, poets were more important than musicians, superior beings all around”. In his later years the only person Beethoven acknowledged as a superior was the poet Goethe. And he eventually “came to call himself not a Komponist but a Tondichter, a tone poet.”

The 2008 theory of everything

A fascinating (and, I think, correct) piece by Sam Freedman arguing that the 2008 financial crash was the event that changed everything and which put the modern world on its current dangerous trajectory:

To fully understand Brexit, Trump, Farage, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, even the large wave of immigration that has transformed European politics, we need to understand how the effects of the crash percolated out into politics, economics and international relations.

The historian Adam Tooze has compared the financial crash to the First World War in its significance: “a moment of total system failure, when an architecture designed to avoid a calamity helped create it, and after which numerous assumptions had to be discarded”.

Freedman’s most interesting observations are about the way the financial crash destabilised geopolitics, something I hadn’t properly grasped before:

To take Syria as an example, the crash led to a drop in remittances from Gulf countries, where many Syrians worked, and a big fall in oil prices which hit government revenue hard. This meant they could no longer afford the substantial fuel and food subsidies that had held popular anger in check, leading to massive price rises. This happened at the same time as a historically bad drought exacerbating the effects. The ferocity of the fighting was, in part, due to the battle hardened jihadis coming back from Iraq and joining rebel forces, but economics was the trigger, as it nearly always is.

That is the link between the financial crash and the refugee crisis. The financial crash was also an important cause of the Ukraine war, as Freedman interestingly explains:

Putin’s ratings started to fall and the first (and only) serious protests against his regime began in 2011 for similar reasons that Middle Eastern governments were coming under pressure. He saw what was happening to Syria and became increasingly paranoid about western intervention in Moscow. His response was to shift his narrative away from economic growth and towards a viciously right-wing nationalism in which the socially liberal west was the main threat.

The crash also made Putin appreciate the economic importance of the post-Soviet sphere to Russia given the volatility of the wider global economy, putting more pressure to keep Ukraine, in particular, dependent on Russia.

Thanks for that, bankers.

Elite education polarisation in the US Senate

Fascinating graph showing the number of American Republican and Democrat senators educated at Yale from 1973 to 2021. A good way of visualising the way American politics has flipped:

Post-literate society latest

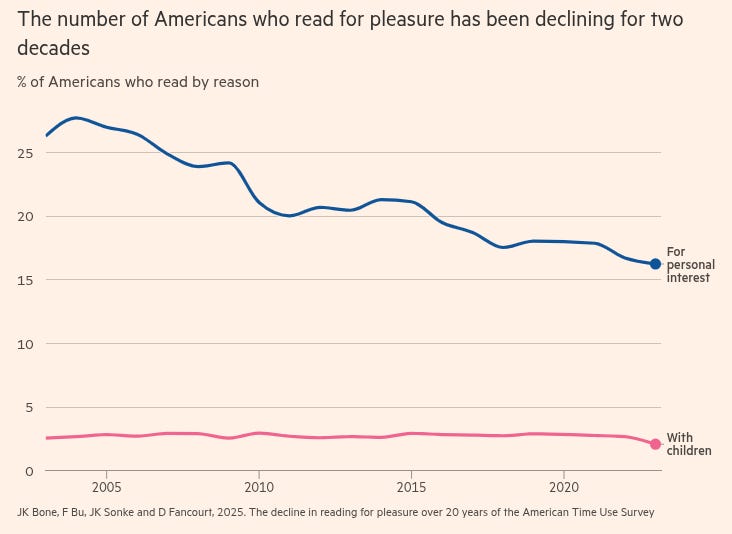

The Financial Times reports on an alarming new study which shows reading for pleasure has fallen by 40 per cent in the last couple of decades:

Analysing data from the US government’s American Time Use Survey, researchers at the University of Florida and University College London found that of the 236,000 Americans surveyed the proportion who read for pleasure on an average day fell from 28 per cent in 2003 to 16 per cent in 2023.

“This is not just a small dip — it’s a sustained decline of about 3 per cent per year,” said Jill Sonke, at the University of Florida. “It’s significant and deeply concerning.”

The stupidogenic society

On the same theme … A few people have pointed out the similarities between the obesity crisis and the present crisis of declining cognitive ability. A few weeks ago in a column I coined the word “moronogenic” to describe the way the world of AI and smartphone addiction makes us stupid the way the “obesogenic” society of MacDonald’s and declining manual labour made us fat.

In an interesting new piece Daisy Christodoulou suggests “stupidogenic”. As she puts it: “The cost of physical machines is human obesity; the cost of intelligent machines is human stupidity.”

She interestingly points out that modern declines in literacy and IQ are foreshadowed to some degree by declines in mathematics and musical ability which were widespread skills before the rise of recorded music and calculators. Christodoulou’s grandmother was a market trader:

Working on a market stall gives you many skills, and one of them was that she was incredibly quick at mental arithmetic. A couple of years before that photo was taken, I remember asking her if I could count some of the coins from a day’s takings. I had seen her do it so many times, and she made it look so easy. After a minute or so, I realised it wasn’t. My hands and my brain just couldn’t work as quickly as hers.

She was not the only one with those skills. Most of the other stallholders were similar. . . Other people of that generation had useful skills too. At least one person in every extended family seemed able to play the piano to a decent standard.

Do younger generations have the same set of skills? Do adults born in the 1980s and 1990s have the same speed at mental arithmetic? Is the ability to play a musical instrument as widespread?

I especially like the idea that as a society gets stupider some people will take up maths problems or adult study in the way marathons and yoga became popular in the 1970s:

Whilst we live in an obesogenic society, there are countervailing trends. Many people have taken up physical activity as a leisure pastime. As recently as the 1970s, joggers used to be laughed at as faddish weirdos, but now Parkrun attracts millions of participants every Saturday morning. People pay money to go to the gym, run marathons and take part in events like Iron Man and Tough Mudder – activities that previous generations would have thought were insane.

Some people alive today are probably fitter and healthier than any in history. And some people are not, and there is a huge range in between. Liberating people from physical toil has led to a much wider range of physical fitness.

Maybe something similar will happen with intellectual fitness. Cognitive games and puzzles and competitions will become very popular. Adults will employ personal tutors and coaches to help them win. Who knows what the intellectual equivalent of Tough Mudder will be.

Interestingly there seems to be some evidence this is already happening. I saw some data recently suggesting that even as reading is declining a minority of people is reading more than ever. The study I mentioned above found that, “For those who already do read, the time spent reading has increased slightly”. Cultural Capital readers who live in London will know the feeling of smugness you get when you’re the only person reading a book on the tube. It is highly motivating.

ChatGPT MPs

There has been speculation that MPs are using ChatGPT in parliament. Apparently in the House of Commons nowadays you can play “AI bingo”, listening out for the common tics ChatGPT uses when writing parliamentary speeches. The most prominent is the phrase “I rise to speak”. And lo and behold Hansard shows there’s been a spike in the use of that phrase over the last year:

Not exactly a golden age of oratory.

Baby Grumpling

Will Lloyd very entertaining on Andrew Lownie’s extravagantly damning new biography of Prince Andrew aka “Baby Grumpling” (a childhood nickname). He sounds like a complete rotter:

Lownie claims Andrew once fired a lackey for having a mole on his face. Another fluffer was dismissed for wearing a nylon tie. Then there is this: “At one dinner party [Andrew] sniffed the pâté served as first course and turned to his right. ‘This pâté smells. What do you think?’ His female companion leaned forward to smell it and he promptly pushed her face into the dish.”

Well, I suppose this is pretty much how we all imagined he behaved. He was even awful as a toddler:

Andrew was marked out from birth by a lack of intelligence. The Queen called her second son “a bit of a handful”, while Philip – in a famous quote that Lownie doesn’t use – once described him as a “natural boss”. Certainly, compared to the otherworldly Charles, Andrew was loud, stupid, devious, spoiled, rude and cruel. Toddler Andrew followed footmen around tugging their tailcoats, climbed up surfaces to take things placed deliberately out of his reach and pedalled furiously along palace corridors on his tricycle.

AI jobs apocalypse latest

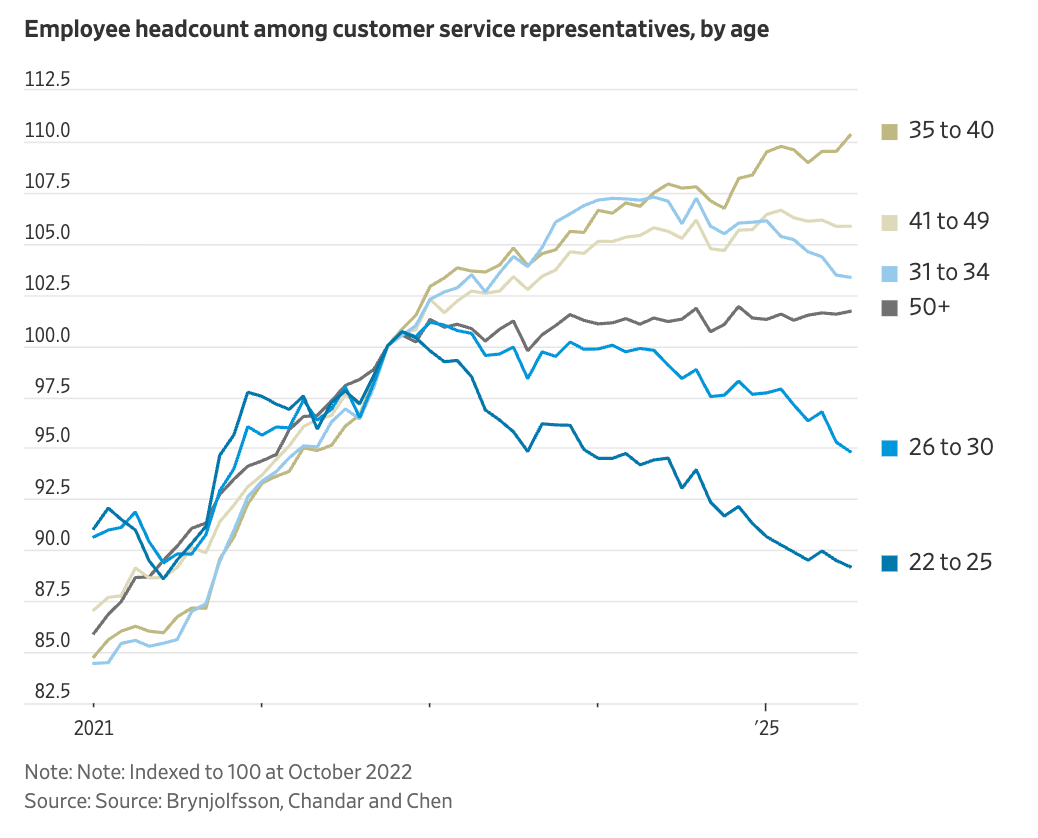

Derek Thompson follows up an interesting new paper from Stanford which finds compelling evidence that AI is beginning to erode entry level jobs:

In a new paper, several Stanford economists studied payroll data from the private company ADP, which covers millions of workers, through mid-2025. They found that young workers aged 22–25 in “highly AI-exposed” jobs, such as software developers and customer service agents, experienced a 13 percent decline in employment since the advent of ChatGPT. Notably, the economists found that older workers and less-exposed jobs, such as home health aides, saw steady or rising employment.

Early career employees are more exposed to AI because the things they know are closer to the kind of things that are in an AI’s training data. As workers progress in their careers they acquire “tacit” knowledge — even become more “human”':

LLMs learn from what’s written down and codified, like books, articles, Reddit, the internet. There’s overlap between what young workers learn in classrooms, like at Stanford, and what LLMs can replicate. Senior workers rely more on tacit knowledge, which is the tips and tricks of the trade that aren’t written down. It appears what younger workers know overlaps more with what LLMs can replace.

Until next time!

James

It's interesting that you say those who read are reading more than ever, as I find that to be true for me and my wife. Also I would argue that the defining event of the century wasn't the financial crisis in 2008 but the advent of the smartphone the year before. All of our current social ills seem to be downstream of that.

Another great post. There is definitely evidence of poets helping other poets, however, ie Sassoon and Owen and Pound and T S Eliot.