Zooming Among the Absolutes

Plus Normans at Oxbridge, mediocrities in power and a dubious millennial saint

Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital. This week in The Times I wrote about why it is that Britain seems to suffer from so many mediocre people in positions of power.

I was also on the Moral Maze attempting to persuade Ash Sarkar of the virtues of cultural elitism — I don’t think very successfully. She called me a “Slytherin”.

*I should also say before I forget that the newsletter will take a two week hiatus as I am going on holiday to France.*

I read a couple of good books last week. Anthony Burgess’s book on DH Lawrence, Flame Into Being was enjoyable but a little flimsier than I’d hoped.

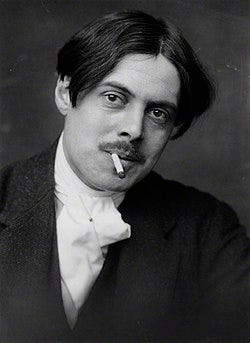

I also read John Carey’s John Donne: Life, Mind and Art. This was a really fantastic book. Formidably intelligent and addictively readable. I think it might be one of the best books I’ve ever read about a poet. It also works as a superb guide to the emotional and intellectual atmosphere of the late sixteenth/early sixteenth centuries — the melancholy, feverish, death-haunted world of John Webster’s plays and Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy.

We’re very lucky to have Carey as a guide to Donne because he can be such a difficult poet — tangled, intellectual, egotistical, gloomy and grotesque. He is famous as a love poet but the love poems are often as much about abstract argument, fantastically overblown metaphors and grotesque flights of fancy as they are about love. Take this famous image of two lovers from The Ecstasie:

Our hands were firmly cemented

With a fast balm, which thence did spring;

Our eye-beams twisted, and did thread

Our eyes upon one double string;

Hands welded together by sweat and eyeballs threaded on a string! Only Donne could put such a bizarre image in a love poem. Christoper Hill called Donne “the most intellectual of English poets”. I agree. But in his vengefulness, obscurity and zaniness and coolness (see picture above) he also sometimes reminds me of Bob Dylan. Indeed, he can make the Dylan of Like a Rolling Stone look like a friendly and generous sort of person:

When by thy scorn, O murd'ress, I am dead

And that thou think'st thee free

From all solicitation from me,

Then shall my ghost come to thy bed. . .

Donne is not a poet I find easy to like (as with, say, Auden or Larkin or Coleridge). You never sense a particularly attractive personality behind his poems. Carey is candid about Donne’s vanity, ambition, callousness and social climbing (he’s constantly writing obsequious and self-promoting letters to wealthy men and women describing himself as “a poor worme” and so on).

But if you are willing to get past the pain barrier of Donne’s difficulty and egotism, the reward is very great. I am such a fan that my father bought me a John Donne-themed espresso cup for my last birthday:

If you’re new to him you need to find a way in. Sometimes I think even an incidental phrase or observation can unlock a poet for you. I remember a university lecturer remarking that it helps to think of Sylvia Plath as the literary equivalent of an expressionist painter — always pushing language to its most garish and violent extremes. And bam! Suddenly Plath fell into place for me and I’ve thought she was a genius ever since. I think Carey’s commentary on Donne’s poem The Feaver might serve a similar purpose for any new readers who are struggling to “get” him:

There is another respect in which ‘A Feaver’ portrays Donne’s demanding nature, apart from its blatant selfishness. The loved girl is not addressed simply as a loved girl. She is accorded universal importance. The world, Donne avows, will evaporate when she dies:

Or if, when thou, the worlds soule, goest,

It stay,’ tis but thy carkasse then,

The fairest woman, but thy ghost,

But corrupt wormes, the worthyest men.This is typical Donnean exorbitance. The upsurge towards the unmatchable is a constant mark of his poetry. His soul felt impelled to reach for peaks and zeniths. It is characteristic, too, that the woman he is writing about should be superseded. We find that, in the excitement, she has been transformed into a cosmic principle, or into a symbol of peerless power and virtue. He balances on the high edge of language, striving to voice the unsurpassable, and the girl, with all her personal particulars, is lost to sight thousands of feet below.

What Donne loves to do, Carey says, is “zoom and spiral freely among the absolutes”. I think that’s a useful phrase to bear in mind while trying to appreciating the abstracted and extravagant weirdness of much of his poetry.

Other Things

The Semantic Apocalypse

Scott Alexander on the “semantic apocalypse” of AI and how technology has been destroying our sense of wonder for centuries:

My lack of appreciation for ultramarine dye is of the same kind as my lack of appreciation for not dying of cholera. Or for coffee - an ordinary latte might blend beans from Ethiopia, Ghana, and Suriname with sugar from Brazil and vanilla from a rare orchid found only in Madagascar; by now, it’s so unbearably boring that you can find dozens of Reddit threads asking how to spruce it up, make it feel new again. We gripe about how LLMs are destroying wonder, never thinking about how we’re speaking to an alien intelligence made by etching strange sigils on a tiny glass wafer on a mountainous jungle island off the coast of China, then converting every book ever written into electricity and blasting them through the sigils at near-light-speed. It’s all amazing, and we’re bored to death of all of it.

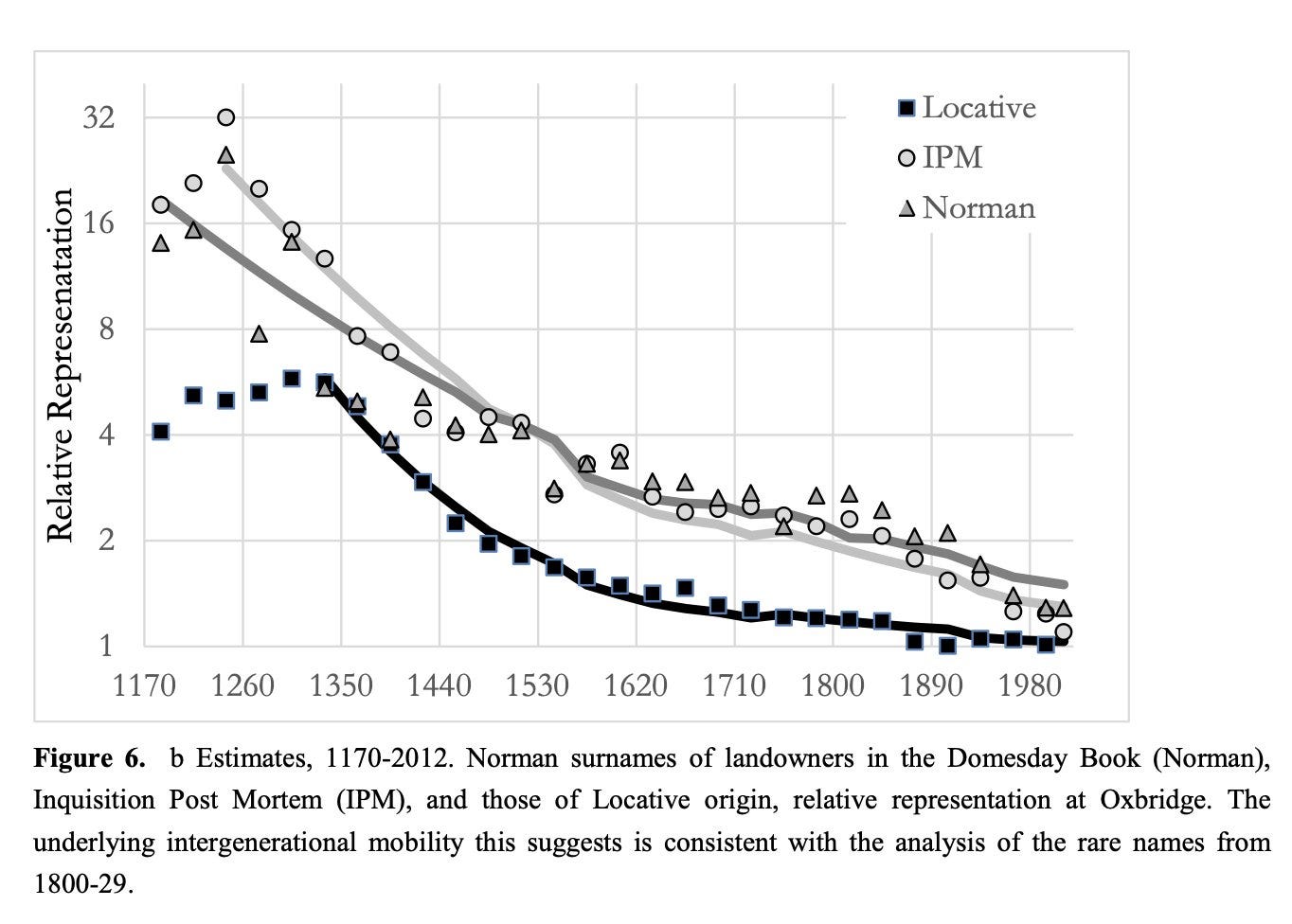

Normans at Oxbridge

This graph shows that “Norman surnames are modestly overrepresented among Oxford and Cambridge students over 900 years after the Conquest”:

Dubious Millennial Saint

Very interesting piece by John Phipps in The Economist about Carlo Acutis, “the first millennial saint” whose canonisation is currently being fast-tracked by the Catholic Church. But it turns out that one of Acutis’s best friends “hadn’t even known Carlo was religious.” It seems that the idea that Acutis was an extremely devout teenager is being pushed by his grieving mother:

I asked [Carlo’s mother] why Carlo didn’t promote his faith to his friends at school. She insisted, almost pleadingly, that Carlo had touched his friends’ lives. “Michele del Vecchio,” she said, “he does volunteering work with the poor now. Did he tell you?” She paused.

“Also the other one. The name is Federico, no?” She talked as though recalling someone she hardly remembered. “He’s more Catholic,” she said, meaning baptised, “but he’s not practising.”

These friends were nothing like her son, she claimed. Carlo could sit for hours in front of the tabernacle in silence. He was a mystic. “They were always talking about pre-marital sex,” she said, dismissively. “Carlo was not of this mind. Carlo had great respect for the body.”

Post Woke White Lotus

I’m enjoying reading people’s reactions to the new series of White Lotus more than I’m enjoying watching the show itself which I’m finding almost intolerably aimless. Helen Lewis is typically interesting on White Lotus as the first post-woke TV show:

Suggesting that cross-dressing has a sexual component is even more subversive than, say, a graphic first-season sex scene featuring the hotel manager and one of his male employees. You might have thought that no taboos were left, but here is something as countercultural as Star Trek’s interracial kiss in the 1960s, or Ellen DeGeneres coming out in a 1997 episode of her sitcom, Ellen. Notably, unlike in the past, a screenwriter seems “brave” today by challenging liberals rather than religious conservatives.

Seamus Perry on Wyndham Lewis

Seamus Perry is one of my favourite living critics. I missed this superb piece on the (decidedly wacky) thought of the writer and painter Wyndham Lewis published in the LRB back in December. How is this for a career-ruiningly bad take:

The great disaster of Lewis’s writing life was a farcically ill-judged book about Hitler, published in 1931, in which, among other things, the Führer was described as ‘a man of peace’. The result was, as he recalled, that he woke one morning to find himself ‘not famous but infamous’.

Christianity and Liberalism Query

I’ve been thinking quite a bit recently about the widely current idea that Christianity, with its unique emphasis on moral equality, is the origin of Western liberalism, tolerance and individualism. This argument (or a version of it) is made by three of my favourite recent non-fiction books, Tom Holland’s Dominion, Joseph Henrich’s The Weirdest People in the World and Larry Siedentop’s Inventing the Individual. But the more I read about the history of religion the more I also get the impression that most major world religions teach moral principles that aren’t radically different to those at the heart of Christianity. I recently visited a Hindu temple near my flat in London and it was plastered in slogans about behaving well towards your neighbours and treating all people equally. In his book The Evolution of God Robert Wright says that all major monotheisms teach a basic altruistic pro-social moral code that evolved to facilitate the cohesion of the increasingly complex societies that emerged in the so-called “axial age”.

I wonder if there is an argument that the origins of liberalism could ultimately be attributed more to material factors than to the influence of religious ideas. What if wealthier societies are simply more tolerant and more individualistic because they are under less material strain? Perhaps Islam would have evolved into liberalism if it had developed in relatively fertile resource-rich western Europe rather than the deserts of Arabia? And after all, for much of Christian history, Christians were just as violent, cruel and intolerant as anyone else — launching crusades and persecuting Jews etc.

Perhaps there is also an argument that it hardly matters what a religious text actually says and people will just interpret any holy book in the way that best suits their personal material interests (e.g. the “prosperity gospel” movement in America which teaches that Jesus will make you rich if you pray hard enough, an idea that is obviously in direct contradiction of the New Testament). It is surely not hard to see how a certain reading of the Koran could be used to support liberal ideas.

Anyway, I clearly don’t know anything about this. It’s just something that I have been wondering about lately. I would love to know the answers to these questions. And I would be interested to know if any readers had any thoughts on the matter or could recommend books that might help.

Poem of the Week: ‘The Anniversarie’ by John Donne

Continuing with the Donne theme… This is one of my favourite Donne poems. I love its gloominess. It is a love poem about celebrating the first anniversary of a relationship, but it’s also about death and decay:

All Kings, and all their favourites,

All glory of honours, beauties, wits,

The sun itself, which makes times, as they pass,

Is elder by a year now than it was

When thou and I first one another saw:

All other things to their destruction draw,

Only our love hath no decay;

John Carey writes beautifully about those opening lines:

The first three lines of the poem, blending kings and glory with the sun, sound like a fanfare to majesty. But they are a dirge. The gorgeous blaze darkens, and the poet’s individual claim springs clear of the dying splendours massed at the start. It is over the wreck of empires and solar systems that the first stanza strides forward.

In the second stanza Donne muses on what will happen when he and his lover die. Carey points out that the fact Donne says they will be buried separately (“Two graves must hide thine and my corse”) suggests this poem is not about his wife Anne More as some people have speculated.

Donne now introduces one of his favourite romantic metaphors, that of political sovereignty (most famously used in the “she is all states and all princes I” lines in the Sun Rising). He and his lover rule over one another like princes, he says. But death comes even to royalty:

Alas, as well as other Princes, we

(Who Prince enough in one another be)

Must leave at last in death these eyes and ears,

Oft fed with true oaths, and with sweet salt tears

When they are souls in heaven, Donne says, they may experience a superior form of love to mere earthly romance (“a love increasèd there above”) . But the galling thing about this is that it will be exactly the same kind of ecstatic love everyone in heaven is experiencing (And then we shall be throughly blessed; /But we no more than all the rest.) And as Carey astutely comments, “it is not happiness but superiority that Donne craves”. The final stanza pushes aside speculation about the afterlife and returns to the metaphor of kingship:

Here upon earth we’re Kings, and none but we

Can be such Kings, nor of such subjects be;

Who is so safe as we? where none can do

Treason to us, except one of us two.

Carey says:

Donne could, of course, have written a simpler poem if he had assumed that he and the girl would go on being kings after death. Then the need to choose between heavenly blessedness and royal supremacy would have been avoided. But he didn’t choose to. He planned his poem so that the frailty, as well as the supremacy, of the kingship it boasts of should be exposed. He pitted love’s kings against unkinging death, so that the poem’s certitude should be tempered by doubt, its ambition by anxiety.

Not an easy poet. But an exceptionally brilliant and interesting one.

Your comparison of Donne with Bob Dylan feels right on lots of levels - but he could also have been the Leonard Cohen of his time…

You are surely right about cultural elites. The idea that "if you like it, it is good" is usually applied to safe areas like books and music. People who admire the egalitarian idea that all books are worthy would be aghast at the application of their principle to things like smoking, excessive alcohol and sugar, drugs, junk food, pornography, bigoted television programmes, the sort of political hatred that is now widespread, etc etc etc.

Of course, many other good reasons can be given for objecting to these things, but must we not ask if beauty is the in eye of the beholder, why not other qualities too?

What this idea fails to account for is knowledge. Someone who lives, Robinson Crusoe like, on an island with little art and few people will find their taste insufficient to the metropolis, and will soon be expanding their taste as their knowledge grows. the democratising cultural force of the internet enables this *as well as * enabling human-produced slop. We shy away from calling it slop, but the reasoning that leads us there is more ideological than rational.

The real problem is not that we have elites, but that they are insufficient. Elites have two functions: to instruct, and to inform. They often, of late, fail at the second, Public health elites are the worst, delivering very little serious information to back up their claims, and allowing one ideology to take precedence over the data. But literary elites are not so far behind. When Zena Hitz praised 4chan readers for reading Moby Dick, the Bible, and Dostoevsky, several literary elites chided her for not talking about modern canon theory, women writers, and so on. The tak of simply telling people that yes, in fact, Tolstoy, Dante, etc are the very best, and should be read, has been too often abandoned.

While we live under such a philistine supremacy (teachers arguing against teaching Shakespeare, book section editors not reading Middlemarch, professor putting Taylor Swift on the syllabus) democratisation will feel chaotic and diminishing. Better elites can turn it into a positive cultural force. This is why Substacks like your are flourishing. Readers just want to know!