Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital. In my Times column, I wrote a paean to the Lit & Phil, the exceptionally beautiful library in Newcastle upon Tyne where I spent virtually half my adolescence. Part of my argument was that libraries are not just utilitarian systems of information dispersal but that they also serve the important symbolic purpose of demonstrating how much the society that built them values knowledge.

Depressing modern libraries which are all grey carpets and grim banks of computers send a message that we do not much respect knowledge — or perhaps that in an age of information overload that have become complacent about its importance.

The Lit & Phil is a temple to knowledge and truth as almost sacred principles:

It’s well worth visiting if you’re ever in Newcastle.

I also wrote an issue of the excellent Substack Eclectic Letters which asks a new writer to contribute recommendations of things they like every week. I nominated my favourite soup, my favourite painting and my favourite LRB essay among other things.

My reading was a bit all over the place last week. On the recommendation of Henry Oliver of The Common Reader I’ve been reading and loving Kenneth Tynan’s Profiles which is a collection of his longer journalism. I’m also reading DH Lawrence’s Twilight in Italy — some people say Lawrence’s travel writing is his best stuff. It’s full of wonderful vivid prose but every so often you have to endure mad bits about how “I drink all blood, until this fuel blazes up in me to the consummate fire of the Infinite. In the ecstasy I am Infinite, I become again the great Whole, I am a flame of the One White Flame” etc.

The Evolution of God

I also read Robert Wright’s book The Evolution of God which was fantastic. Wright traces the development of religion from animistic hunter gatherer beliefs to the development of monotheisms like Christianity, Judaism, Atenism and Islam.

Ancient Israel

Most people are aware that Judaism evolved out of a polytheistic religion that has left traces of its existence in the Bible. I still find it fascinating to read about:

. . . even Israelites who didn’t worship gods other than Yahweh still believed in their existence. Early affirmations of devotion to Yahweh don’t single him out for being the only god, just for being the best god for the Israelites, the one you should worship. That ancient hymn to Yahweh, “man of war,” asks this question: “Who is like thee, O Lord, among the gods?” Indeed, the Bible sometimes mentions other gods matter-of-factly. In the book of Numbers, for example, when the Moabites are conquered, it says that their god Chemosh “has made his sons fugitives, and his daughters captives.

Wright points out that in the earliest Bible passages, God doesn’t seem like the remote, disembodied, omniscient deity we are familiar with today. Rather he appears much more like one of the human-like gods familiar from the other cultures in the ancient world:

In fact, even in the first millennium BCE, when most if not all of Genesis took shape, God was a hands-on deity. He personally “planted” the Garden of Eden, and he “made garments of skins” for Adam and Eve “and clothed them.” And he doesn’t seem to have done these things while hovering ethereally above the planet. After Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit, according to Genesis, “they heard the sound of the Lord God walking in the garden at the time of the evening breeze, and the man and his wife hid themselves from the presence of the Lord God among the trees of the garden.” Hiding may sound like a naïve strategy to deploy against the omniscient God we know today, but apparently he wasn’t omniscient back then. For “the Lord God called to the man, and said to him, ‘Where are you?’” In short, Yahweh is at this point remarkably like all those “primitive” gods of hunter-gatherer societies and chiefdoms: strikingly human—with supernatural power, to be sure, but not with infinite power.

Wright attributes Judaism’s evolution into a monotheistic religion to the difficult geopolitical position of ancient Israel. Societies with good relationships with their neighbours tended to tolerate each other's gods. Israel was continually assailed by enemies and developed a kind of theological nationalism whereby Yahweh was not only better than other gods, but the only god that existed. There was also a fatalistic comfort in imagining that although disasters kept befalling Israel, Yaweh was behind it all as the master puppeteer of history directing even the actions of Israel’s enemies in order to achieve some unseen cosmic purpose.

Historical Jesus

I also love reading about the historical Jesus. Wright is especially harsh on him. It’s commonly agreed among secular scholars that Jesus considered himself a Jewish prophet not the founder of a new religion. We owe Christianity as a religion with its unique emphasis on moral universalism and love to St Paul. Wright suggests that Jesus himself may have been in some ways actively opposed to these fundamental ideas. He suggests that on the evidence of Mark ‘the oldest and most reliable of the gospels’, Jesus emerges almost as a kind of nationalist:

In the book of Mark, the word “love” appears in only one passage. Jesus, asked by a scribe which biblical commandment is foremost, cites two: “The first is… ‘you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.’ The second is this, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’” When the scribe agrees and deems these commandments “more important than all whole burnt offerings and sacrifices,” Jesus says, “You are not far from the kingdom of heaven.”

This is definitely a message of love. But love of what breadth? We’ve already seen that in the verse Jesus quotes—the Hebrew Bible’s injunction to love your neighbor—the meaning of “neighbor” was probably confined to other Israelites. In other words: neighbor meant neighbor. There is no obvious reason to believe that this part of the earliest gospel, the only part of Mark where the word “love” shows up at all, was meant more expansively.

In fact, there is reason to believe otherwise. Two gospels carry the story of a woman who asks Jesus to exorcise a demon from her daughter. Unfortunately for her, she isn’t from Israel. (She is “Canaanite” in one gospel, “Syrophoenician” in another.) Jesus takes this into account and replies, with one of his less flattering allegories, “It is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.” Pathetically, the woman answers, “Yet even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters’ table,” after which Jesus relents and tosses her some crumbs by tossing out the demons.

St Paul

In fact, Wright doesn’t even let St Paul off the hook, arguing that his emphasis on “love” often derives less from a sublime new theology and more from a need to manage squabbling factions in the early church:

There is a second and possibly related problem. Many in the church—“enthusiasts,” some scholars call them—believed themselves to have direct access to divine knowledge and to be near spiritual perfection. Some thought they needn’t accept the church’s guidance in moral matters. Some showed off their spiritual gifts by spontaneously speaking in tongues during worship services, something that might annoy the humbler worshippers and that, in large enough doses, could derail a service. As the scholar Gunther Bornkamm has put it, “The mark of the ‘enthusiasts’ was that they disavowed responsible obligation toward the rest.”

In other words: they lacked brotherly love. Hence Paul’s harping on that theme in 1 Corinthians and, especially, in chapter 13 (the “love chapter,” which has figured in so many weddings). In light of this context, the language in that chapter makes a new kind of sense. It is in reference to disrupting worship by speaking in tongues that Paul writes, “If I speak in the tongues of mortals and of angels, but do not have love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal.” And when he says that “love is not envious or boastful or arrogant,” he is chastising Corinthians who deploy their spiritual gifts—whether speaking in tongues, or prophesying, or even generosity—in a competitive, showy way.

Important disclaimer

I am emphatically not saying that any of this is necessarily the correct interpretation of the Bible, only that I find it interesting. No theological arguments in the comments unless it is extremely calm and respectful!

Other Things

The Evolution of Anger

Rob Henderson is interesting here on the evolutionary psychology of anger. High status people get angrier more often:

Research led by the psychologist Aaron Sell reveals interesting patterns regarding what predicts propensity for anger. In one study, he measured how much weight male participants could lift and compared it to their likelihood of expressing anger and aggression. He found stronger men were consistently more prone to anger—not just in American samples, but also among hunter-gatherer groups in Peru and central Africa. Anger appears to be a particularly effective bargaining strategy for physically strong men.

Interestingly, this pattern didn’t hold for women. Instead, women's anger correlated with popularity and attractiveness rather than physical strength. Attractive and popular women are more likely to express anger, relative to less attractive women, presumably by withdrawing benefits (as opposed to inflicting costs, as men tend to do).

Steven Pinker and Ian McEwan on how to write

I enjoyed this conversation between Steven Pinker and Ian McEwan on how to write well. The most useful advice for effective writing I have ever been taught was that you have to “put an image in your reader’s mind”. Concrete images are much more engaging than vague abstractions. McEwan cites a similar principle from Joseph Conrad who said, “My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel — it is, before all, to make you see.”

English without the Normans

Very fun piece by Ed West on what the English language would look like if the Norman invasion had never happened. As we all know, the Normans introduced all kinds of French-derived words into the language, making English a much less Germanic language than it would have been otherwise. It’s an intriguing alternate reality:

In this world, lamentation is sorrowword, unanimous becomes sameheart and acceptable is replaced with thankworthy. The US Declaration of Independence would be the ‘Forthspell of Selfdom’ while Alcoholics Anonymous renamed as The Unnamed Overdrinkers.

Even spellings would be markedly different; there is no gh combination in this version of English so we have noiht and soiht. The letter C would never be pronounced as an S, and there is no ‘Q’, so the king is married to the cween.

Cowley suggested mislikeness for different, bethought for planned, inherd for family and werekin for human race. Fertility would be replaced by bearingness, while community is meanship. A moderate improvement becomes a metefast bettering, frivolity becomes lightmoodness, while modesty is shamefastness.

Their horses also are swifter than leopards

In his book Robert Wright quote some splendidly hair-raising lines from the Old Testament prophet Habakkuk which reminded me of one of my all time favourite pieces of English church music, Stanford’s anthem For Lo I Raise Up:

English church music for all its loveliness often sounds parochial, putting you in mind of meadows and country lanes not ancient Israel. But I think in this piece of music Stanford really does capture something of the ancient terror in the Biblical words. And they are incredible words:

For lo I raise up that bitter and hasty nation,

Which march thro' the breadth of the earth,

To possess the dwelling places that are not theirs.

They are terrible and dreadful,

Their judgment and their dignity proceed from themselves.

Their horses also are swifter than leopards,

And are more fierce than the evening wolves.

And their horsemen spread themselves,

Yea, their horsemen come from far.

They fly as an eagle that hasteth to devour,

They come all of them for violence;

Their faces are set as the east-wind,

And they gather captives as the sand.

I’ve been listening to it on repeat all week.

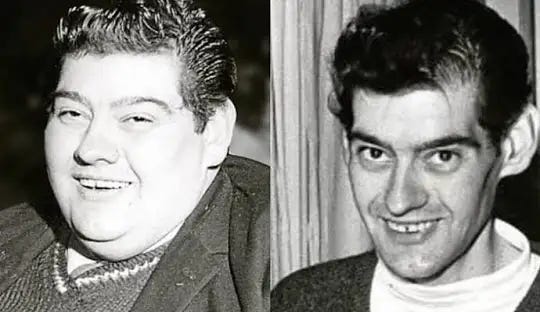

The man who ate nothing for a year

Apparently if you are incredibly fat it is scientifically possible to eat nothing for a year. Angus Barbieri didn’t eat for a year and went from 456 lbs to 180lbs:

In 1965, at the age of 27, Barbieri checked into the Maryfield Hospital in Dundee. Initially only a short fast was planned, due to the doctors believing that short fasts were preferable to longer ones. Barbieri insisted on continuing because "he adapted so well and was eager to reach his 'ideal' weight".[2]: 203 To avoid temptation, he quit working at his father's fish and chips shop, which closed down during the fast. As the fast progressed, he lost all desire for food.[4] For 382 days, from 14 June 1965 through 30 June 1966, he consumed only vitamins, electrolytes, an unspecified amount of yeast (a source of all essential amino acids) and zero-calorie beverages such as tea, coffee, and sparkling water, although he occasionally added milk and/or sugar to the beverages, especially during the final weeks of the fast.

And he kept the weight off!

Poem of the Week: ‘The Beautiful Librarians’ by Sean O’Brien

While we’re eulogising libraries in Newcastle, I have a lot of time for the Newcastle-based poet Sean O’Brien. He has a lovely poem about libraries, The Beautiful Librarians. It does not really require a great deal of explication. The speaker recalls how (presumably in adolescence) he wordlessly admired the beautiful custodians of his local library:

Once I glimpsed the staffroom

Where they smoked and (if the novels

Were correct) would speak of men.

I still see the blue Minis they would drive

Back to their flats around the park,

To Blossom Dearie and red wine

The librarians represent a world of provincial glamour and provincial erudition that is long vanished. I think the last stanza, in which the poet promises he will keep faith with that lost world, is very effective indeed:

Never to even brush in passing

Yet nonetheless keep faith with them,

The ice queens in their realms of gold –

It passes time that passes anyway.

Book after book I kept my word

Elsewhere, long after they were gone

And all the brilliant stock was sold.

You are right about libraries. Sadly Kirklees Council shut Huddersfield's excellent interwar library and replaced it with a 'hub' in the civic centre https://www.ribapix.com/public-library-huddersfield-west-yorkshire_riba73907

Very interesting column James, thank you. I wonder if the Wright book is a modern version of The Golden Bough?