The first communications revolution

Plus WB Yeats, the worst debate I've ever heard and domesticated fruit

Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital. I wrote my column this week about VE day and Europe’s long peace. In his superb book Political Order and Political Decay, Francis Fukuyama makes the point that a lot of tolerant, stable, liberal democracies were forged in the two hundred years of war and revolution that engulfed Europe after the mid-eighteenth century. War obviously causes terrible damage and suffering but Fukuyama argues that in the long run it has also contributed to making some societies more socially mobile, more democratic and more efficient. This is not (before anyone tries to cancel me) a pro-war column, just a column about how a long peace brings its own unique problems to which European nations are historically unaccustomed.

I also finished Elizabeth Eisenstein’s The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe. A great book and very highly recommended. The topic sounds dull but it’s not at all. There is a lot of fantastic writing on this subject. In the sixties and seventies as television began to saturate our culture, a number of extremely interesting thinkers (notably Marshall MacLuhan and Walter Ong) turned their attention to way revolutions in communication — e.g. the invention of writing and the invention of printing — transform our societies and our minds.

Eisenstein makes a number of interesting arguments. I liked her point that printing tended to undermine teachers and other authority figures:

After the advent of printing, however, the transmission of written information became much more efficient. It was not only the craftsman outside universities who profited from the new opportunities to teach himself. Of equal importance was the chance extended to bright undergraduates to reach beyond their teachers’ grasp. Gifted students no longer needed to sit at the feet of a given master in order to learn a language or academic skill. . . Students who took advantage of technical texts which served as silent instructors were less likely to defer to traditional authority and more receptive to innovating trends. Young minds provided with updated editions, especially of mathematical texts, began to surpass not only their own elders but the wisdom of ancients as well.

The proliferation of books caused by printing meant that people increasingly spent time with a wide variety of texts (and authorities) rather than devoting their lives to eking meaning out of one text:

To consult different books it was no longer so essential to be a wandering scholar. Successive generations of sedentary scholars were less apt to be engrossed by a single text and expend their energies in elaborating on it. The era of the glossator and commentator came to an end, and a new “era of intense cross referencing between one book and another” began.

To such readers, the world looked much more contradictory and various than it had to the men and women whose ideas were dictated by one book (or small handful of books). This tended to weaken the power of established authorities (the analogy with social media hardly needs making) and promote new ideas:

Contradictions became more visible, divergent traditions more difficult to reconcile. The transmission of received opinion could not proceed smoothly once Arabists were set against Galenists or Aristotelians against Ptolemaists. Not only was confidence in old theories weakened, but an enriched reading matter also encouraged the development of new intellectual combinations and permutations.

Montaigne — whose essays are characterised by their open-mindedness about human nature — was one man influenced by the new expanded access to different sources of information:

That he could see more books by spending a few months in his tower study than earlier scholars had seen after a lifetime of travel also needs to be taken into account. In explaining why Montaigne perceived greater “conflict and diversity” in the works he consulted than had medieval commentators in an earlier age, something should be said about the increased number of texts he had at hand.

Another important part of Eisenstein’s argument is printing’s role as a catalyst of the scientific revolution. She argues that the crucial factor was that scientists suddenly had access to multiple data sets which they could collate and compare. And the information in those data sets was much more accurate as it was less subject to the inaccuracies and mistakes inherent in scribal transmission. She cites the case of the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, whose advantage over his predecessors was not a newfangled telescope but better access to better data:

Already while Tycho was a youth of sixteen years of age his eyes were opened to the great fact which seems to us so simple to grasp but which escaped the attention of all European astronomers before him that only through a steadily pursued course of observations would it be possible to obtain a better insight into the motions of the planets. Tycho’s “eyes were opened” to the need for fresh data partly because he had on hand more old data than young students in astronomy had had before. Even as an untutored teenager he could compare Copernicus with Ptolemy and study tables derived from both. Contradictory predictions concerning the conjuction of planets encouraged him to reexamine the “writing in the skies.” For the purpose of gathering fresh data, he was also supplied with newly forged mathematical tools which increased his speed and accuracy when ascertaining the position of a given star. In these and other respects, Tycho’s case does not entirely fit that of “an astronomer who saw new things while looking at old objects with old instruments.” Printed sine tables, trigonometry texts, and star catalogues did represent new objects and instruments in Tycho’s day. As a self-taught mathematician who mastered astronomy out of books, Tycho was himself a new kind of observer.

Like his predecessors, he had no telescope to aid him. But his observatory, unlike theirs, included a library well stocked with printed materials as well as assistants trained in the new arts of printing and engraving.

A few other things

The AI Crisis in Universities

Depressing piece about how ubiquitous ChatGPT is in universities — using AI to write essays is extremely widespread. This chimes with everything I have heard from academics and students I’ve spoken to. This is a bit dystopian:

Toward the end of the semester, she began to think she might be dependent on the website. She already considered herself addicted to TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, and Reddit, where she writes under the username maybeimnotsmart. “I spend so much time on TikTok,” she said. “Hours and hours, until my eyes start hurting, which makes it hard to plan and do my schoolwork. With ChatGPT, I can write an essay in two hours that normally takes 12.”

An illiterate workforce doesn’t sound magnificent:

It isn’t as if cheating is new. But now, as one student put it, “the ceiling has been blown off.” Who could resist a tool that makes every assignment easier with seemingly no consequences? After spending the better part of the past two years grading AI-generated papers, Troy Jollimore, a poet, philosopher, and Cal State Chico ethics professor, has concerns. “Massive numbers of students are going to emerge from university with degrees, and into the workforce, who are essentially illiterate,” he said. “Both in the literal sense and in the sense of being historically illiterate and having no knowledge of their own culture, much less anyone else’s.” That future may arrive sooner than expected when you consider what a short window college really is. Already, roughly half of all undergrads have never experienced college without easy access to generative AI. “We’re talking about an entire generation of learning perhaps significantly undermined here,” said Green, the Santa Clara tech ethicist. “It’s short-circuiting the learning process, and it’s happening fast.”

How many classic novels have you read…

From Penguin’s quite arbitrary list of 100? Silly but fun. I only scored fifty but maintain the list is a bit random and full of not very good books! I would say that of course…

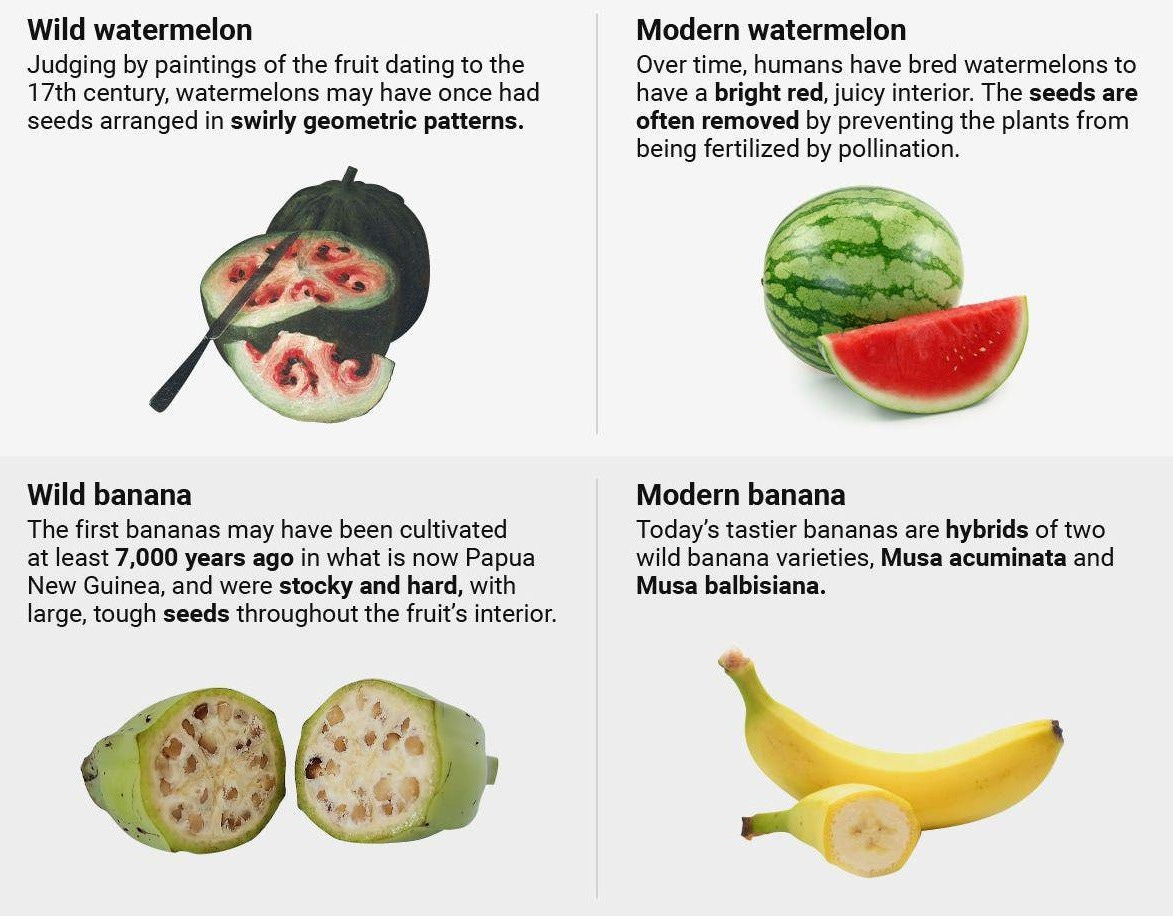

Domestication of fruit

I’ve been listening to the audiobook of Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel. Thoroughly enjoyable. He goes on a lot about the importance of the domestication of plants and I went down a bit of rabbit hole on the subject. Fruit has changed so much. Quite extraordinary.

The worst debate I’ve ever heard

Deborah Frances-White of the Guilty Feminist podcast (woke) debates Konstantin Kisin of Triggernometry (anti-woke). It’s so bad it’s actually weirdly hypnotic. They make stupid points, pointlessly nitpick and performatively refuse to understand each other. It’s like listening to Twitter out loud. Ironically Frances-White’s new book is about “how to have better conversations”. The best bit comes at the end when she tries to win the debate by passive-aggressively psychoanalysing Kisin. I wrote about it here but it’s worth watching if you can bear it. A masterclass in how not to have an argument.

Hopefully not the worst debate you’ve ever heard

I appeared on the Breaking Beliefism podcast, hosted by Paul Dolan, who is a very interesting behavioural scientist at the LSE. This was recorded at the end of last year and I have no memory of what we talked about. “Organised fun, posh restaurants and political shifts among younger generations”, apparently. If you think I’m talking a load of nonsense blame my past self not my present one.

Poem of the Week: The Song of Wandering Aengus by WB Yeats

I don’t usually get on with Yeats — so twee and precious and faux-mythological — but I unexpectedly found myself enjoying this poem. I tend to find this sort of thing intolerably silly:

[I] hooked a berry to a thread;

And when white moths were on the wing,

And moth-like stars were flickering out,

I dropped the berry in a stream

And caught a little silver trout.

But I find that it’s annoying me less. Perhaps I need to crack open my selected Yeats again and have another go.

Talking of cross-pollination and AI-illiteracy, I think you’d enjoy Ian Leslie’s latest Sub-missive:

https://open.substack.com/pub/ianleslie/p/seven-features-of-post-literate-politics?r=43jrc&utm_medium=ios

Enjoy may not be quite the right word, as he examines the online replacing of writing by video - and the way this explains the success of Trump’s communication style: a move back to simple, repeated claims echoing the pre-literate world of Homer etc… I found it chillingly believable.

Terrific stuff on the impact of the printing press (feeling our capacity to learn) and the early signs of AI (doing the opposite). Thank you, James.