Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital. Last week I read and loved Tim Blanning’s social and cultural history of the “long” eighteenth century, The Pursuit of Glory: Europe 1648-1815. I read his excellent book The Romantic Revolution last year. I highly recommend both books. There is a certain kind of middle aged man who will plough through any book about tanks, guns, Nazis and World War II. I have this with cultural history. It is, as they say, crack to me. I would have happily read The Pursuit of Glory at double the length.

Something that fascinates me about the eighteenth century is how artificial and strange it can seem through modern eyes — European court culture, the paintings of Fragonard, the cult of politeness etc. We are looking into a lost world through a distorting glass, from the other side of the Romantic movement and its emphasis on spontaneous feeling, passion and authenticity. These attitudes are now part of our culture and part of us. They shape the way we see the world.

Anyway, here a few favourite bits from Blanning’s book.

Blanning points out that though the eighteenth century is popularly referred to as “the age of reason”, it was also the age of faith. Popular emotional religious movements like Methodism and Pietism flourished. And though we associate monastic life with the middle ages, the eighteenth century might reasonably be described as the golden age of monasteries — there are beautiful baroque monasteries all over continental Europe. What is particularly interesting is quite how many monks and nuns there were:

By the middle of the eighteenth century, one in every hundred inhabitants of the Italian peninsula was a monk or a nun. That was just the average. In certain cities, the clerical presence was much more obtrusive, and not only in Rome. In 1781 there were more than 100 male monasteries in the city of Naples housing 4,617 monks, and nearly 100 convents housing 5,871 nuns. As the total population amounted to 376,000, one in every thirty-six inhabitants was a member of the regular clergy. Their share of the adult population was, of course, much higher.

Nevertheless, I still find the first signs of the dawning age of reason the more interesting story. There is something quite moving about the intellectual honesty and independent-mindedness of this seventeenth-century French unbeliever:

A Parisian parish priest was told by one of his parishioners, a lawyer: ‘Sir, I am in no state to confess my sins or receive the sacraments, although you were good enough to clarify my difficulties on the Christian religion which I have professed externally to avoid notice and save appearances. In the bottom of my soul I feel it is all a fairy tale. And I am not alone in this: 20,000 other people in Paris share my views. We know each other, we hold secret meetings, and we strengthen each other in our irreligious resolve.’

Things had changed by the end of the eighteenth-century:

If a single incident has to be found to mark the culmination of the culture of reason, a strong candidate is an event at Paris on 30 March 1778. For once, that overworked word ‘apotheosis’ is entirely appropriate. For it was on that day that Voltaire went to the Théâtre Français to attend a performance of his final play, Irène. His arrival was greeted with a standing ovation that lasted twenty minutes. When the performance was over, his bust was installed on stage and crowned with a laurel wreath, as the actress playing Irène recited a poem promising Voltaire immortality in the name of the French nation – and then was obliged to give an encore. This was the climax of a triumphal progress across France which had begun the previous month. John Morley observed: ‘no great captain returning from a prolonged campaign of difficulty and hazard crowned by the most glorious victory, ever received a more splendid and far-resounding greeting’. When he arrived at the barrière at the city limits of Paris, he told the customs officer inspecting his belongings: ‘I am the only article of contraband here.’ This remark was very much to the point, for he had been kept out of Paris for thirty years

The dawn of mass literacy is always interesting to me. I especially love to read stories of how much people disapproved of reading when the practice first became widespread:

By the middle of the eighteenth century, reading was being described as ‘an addiction’, ‘a craze’, ‘a madness’: ‘No lover of tobacco or coffee, no wine drinker or lover of games, can be as addicted to their pipe, bottle, games or coffee-table as those many hungry readers are to their reading habit’, observed the Erfurt clergyman Johann Rudolf Gottlieb Beyer. Conservatives were appalled, and progressives were delighted, that it was a habit that knew no social boundaries. A German periodical, the Deutsches Museum, recorded in 1780: ‘Sixty years ago the only people who bought books were academics, but today there is hardly a woman with some claim to education who does not read.

The proliferation of books brought with it a shift from “intensive” to “extensive” reading:

Because there were now so many more books available, both the readers and the way in which they read changed. When few titles were produced in small and expensive editions, the texts were read again and again, mainly for the purposes of devotion, instruction and edification. The typical readers were the priests with their breviaries, the lawyers with their handbooks or the faithful with their bibles. In short, they read intensively. Once there were thousands of titles available, produced in larger and cheaper editions, new kinds of readers joined in, looking for topical information, practical advice and recreation, reading a book once and then discarding it. In short, they read extensively.

Other Things

Notes on a Thesis

Last week I also had a very good time re-reading what might be the most French book ever: a graphic novel about a Parisian student writing a PhD on Kafka. It’s funny on the horrors of academia and procrastination. I first came across it years ago in Foyles. It stuck with me and I finally bought a copy. You can get through it in an afternoon. Rachel Cooke wrote a very good review of it in The Guardian, calling it “the funniest book about academia in years”.

Wagnerism

I’m listening to an audiobook of Alex Ross’s book Wagnerism about the cultural impact of Wagner’s music. I rarely listen to audiobooks but I’m absolutely loving this one. It has been nicely done with clips of Wagner’s music interpolated into it. If you subscribe to Spotify you can listen to it for free. The story is a fascinating one. From some angles almost all of nineteenth and twentieth-century high culture seems to have been produced in response or reaction to Wagner. He is everywhere: in Baudelaire, in The Waste Land, in Mahler, in symbolism, in the decadent movement, even in George Eliot.Perhaps I will expand these thoughts for a future newsletter.

Norman Foster

Ian Parker, the great New Yorker profile writer, has a new piece out about the 89-year-old architect Norman Foster (the Gherkin, the Millennium Bridge, the Apple campus etc). Very instructive on how architecture works and how and why big, expensive buildings get built:

Foster’s overarching achievement is his company. He traded on a refined reputation without losing it; he built an architectural machine that could execute acclaimed, precise work at an unprecedentedly high volume. Foster was the first in the profession to dismantle the distinction between two kinds of architectural success: that of the architect-auteur (giving furrowed attention to a few exceptional projects—cathedrals and concert halls) and that of the big, anonymous corporate practice (designing the malls, towers, hospitals, and rail stations that fill up much of the space that remains). Foster’s production line spits out dozens of structures every year. These will include hospitals and rail stations but also, say, a luxury yacht, or an open-air chapel, for the Vatican, on the Venetian island of San Giorgio Maggiore.

Ed West on Vietnam

I am a great fan of Ed West’s travel writing. He always seems so curious and thoughtful about wherever he is (very far from a given in this genre). He’s just written about Vietnam:

Today [Vietnam’s] GDP per capita is around $4,900, which makes it still a poor country, but there are poor countries which look like they’re going to stay poor, and there are poor countries which are clearly heading in the right direction. Vietnam’s year-on-year growth in the 2010s averaged about 6.5 per cent, and it is trajectory is obvious just by the frenetic early-morning activity in the streets which we saw as we made our hair-raising drive into town.

. . .

The sensory experience of Hanoi is quite overwhelming, in particular the insanity of the traffic, and crossing a busy street can be alarming. The children were soon in tears, made worse by my panic.

The city is shabby but colourful, overflowing with life from the bugs up. You see crowded vegetable shops at the basement of five-story grey concrete blocks with plants growing everywhere; most of the streets are a jumble of three, four and five-story shacks besides the occasional colonial era apartment blocks, with towels hung everywhere. Many of the cars, notably, are brand new.

Viscous Canadian Oil

I always have the vague impression (derived I think from reading Helen Thompson) that if I can properly understand oil I will understand everything about geopolitics and the world will make sense to me. This fascinating piece from Ed Conway shows oil is far too complicated for me ever to understand. Crucial to the ruckus over Trump’s tariffs on Canada was the fact that despite the fact the USA is a net exporter of oil, they actually import a lot of oil from Canada because Canadian oil is more viscous. It’s all to do with what kinds of refining technologies countries have. Weirdly compelling stuff. It sounds like wine tasting:

Most American refineries are set up for the kinds of heavy, sour crudes you get from Canada, Mexico and Venezuela. That made sense when it looked as if the US was running out of domestic oil, but then came the shale oil revolution. American shale oil, it turns out, is typically light and high quality, meaning it is not best-suited for domestic refineries. The upshot is that while arithmetically America is energy independent – producing far more oil than it consumes – in practice it is anything but. It must keep sucking in heavy oils from elsewhere to feed its refineries while sending Texan crude off to Europe and Asia to be refined.

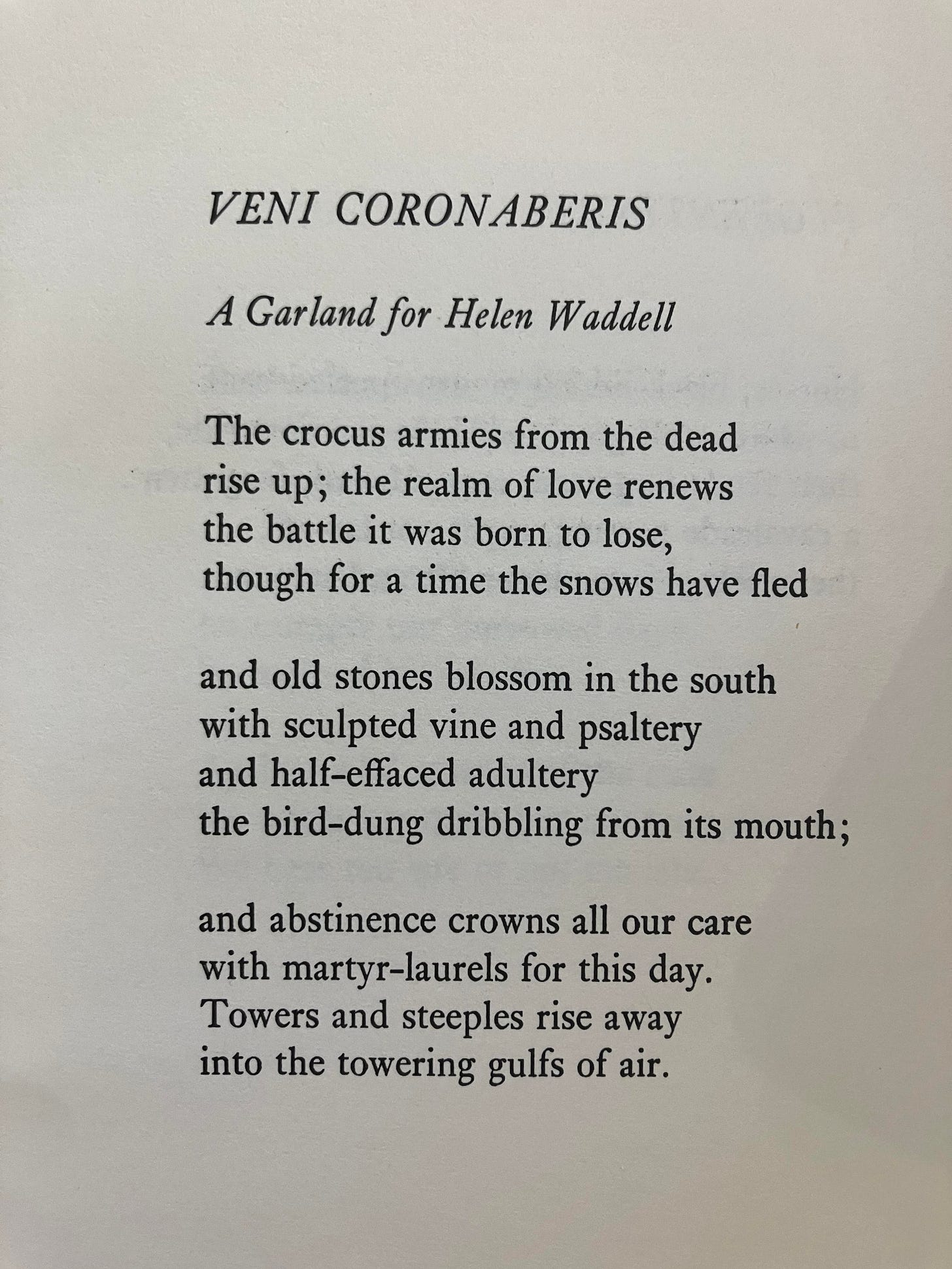

Poem of the Week: Veni Coronaberis by Geoffrey Hill

I have spotted my first crocuses which always put me in mind of this beautiful Geoffrey Hill poem. It’s one of my favourites of his though I am not confident that I understand more than fifty per cent of it.

Here is some useful preliminary information. The poem seems to be roughly about spring and rebirth. The title is a quotation from the Biblical Song of Songs and means “come and be crowned”. It supplies the refrain of a fifteenth-century hymn to the Virgin Mary. I suppose the relevant feast is the Annunciation. The dedication is to Helen Waddell, the poet and scholar of medieval Latin poetry. I once had a debate about the meaning of this poem on Twitter and it was suggested to me that the theme of rebirth has something to do with the re-invigoration of Latin poetry in the middle ages. Or the Carolingian Renaissance? Frankly, who knows? Readers with further clues should leave them in the comments. And, anyway, you don’t need any context to appreciate the ravishing opening stanza:

The crocus armies from the dead

rise up; the realm of love renews

the battle it was born to lose

though for a time the snows have fled

The grandeur and melancholy of “armies”, “realms” and “battle” is a beautiful and unusual way to write about spring. It sends shivers down my spine. I’m convinced that if Hill had chosen not to write half his poetry in the form of ultra-highbrow crossword clues he could have been one of the most widely loved poets of the last century.

The poem gets a little more incomprehensible after this. I don’t think it matters whether or not you understand exactly what he means about bird dung dribbling from the mouth of half-effaced adultery. It works emotionally and is somehow resonates with the promise of spring.

The full poem:

With thanks to Sylvia Crookes for proofreading.

That Hill poem always comes to my mind too, although I habitually misremember the first line as 'Crocus armies of the dead' which is quite different.

I think there are two versions of this poem with a different title and final stanza. The other is called 'Ecce tempus' which is a medieval Lenten hymn, 'Now is our healing time' or something like that. I think that may help to unpick the puzzle with the alternative final stanza:

and abstinence crowns all our care

with martyr-laurels for this day.

The towers of Cluny what are they?

The flowers of Cluny as they are.

I think the stones of the south with their carved vines and lyres represent the sensual, alluring ancient world and our longing for it, the 'half effaced adultery' meaning classical scenes of debauchery worn away by the weather and nesting birds. In contrast, in this time of Lenten healing, we have abstinence and another kind of love with the great promise that that offers to Christians. One world replaces the other, but the distinction between them is uneasy and emotionally ambivalent for creatures that live in and are part of the realm of love of both kinds.

Cultural Capital has quickly become one of the highlights of my week, and hasn’t disappointed this time - thank you.

Can I also recommend the These Times podcast (Tom McTague and Prof Helen Thompson), which looks at current issues from a historical view? For example, the recent episode where they explore the wide-ranging roots of Trump’s lascivious gaze at Greenland I found deeply fascinating.