Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital. I wrote my column this week on why digital distractions represent a public health crisis analogous to the obesity epidemic which emerged in the 1970s.

I also read a couple of books. The first was Ann Wroe’s non-chronological biography of Shelley, Being Shelley (more on that below). The second was Jared Diamond’s brilliant book about hunter gatherer life, The World Until Yesterday. Much of it is based on his work with hunter gatherers in New Guinea such as the Dani people.

It’s become fashionable to believe our species was happiest when we all lived in our original “state of nature” in nomadic hunting bands before our lives were ruined by the invention of agriculture and the advent of civilisation (an idea which begins with Rousseau and was most recently re-popularised by Yuval Noah Harari’s mega-seller Sapiens).

For a while I was quite convinced of this and thought I would like to be a hunter gatherer — though I tended to envision myself in a more sedentary role such as shaman or oral poet.

Of course, the truth turns out to be complicated. On many issues there is no unanimous “hunter gatherer way”. E.g. some beat their children, others are horrified by the very idea. Diamond argues one of the main benefits of hunter gatherer is that is intensely and incessantly social in a way that seems to make people in traditional societies more emotionally secure than insecure, individualistic westerners. Hunter gatherer bands are also much more egalitarian than modern societies. But the idea that hunter gatherer life was a peaceful idyll is sadly a fantasy.

Diamond writes that hunter gatherers find it easier to kill other human beings than people raised in modern civilisations:

Men in traditional societies grow up from childhood encouraged to kill, or at least knowing how to kill, but most modern state citizens grow up taught constantly that killing is bad, until after age 18 they suddenly enlist or are inducted into the army, given a gun, and ordered to aim at an enemy and shoot him. Not surprisingly, a significant fraction of soldiers in World Wars I and II—some estimates run as high as one-half—could not bring themselves to shoot an enemy whom they saw as another human being. Thus, while traditional societies lack both the moral inhibitions against killing an enemy face-to-face, and the technology necessary to bypass those inhibitions by killing unseen victims at a distance, modern state societies have tended to develop both the inhibitions and the technology necessary to bypass the inhibitions.

Our Western culture is saturated by Christian ideas about the sanctity of life. But in hunter-gatherer societies, the value of a life is more dependent on its practical usefulness than its inherently sacred quality. People at the beginning and end of their lives can be killed with fewer qualms than in the modern West. The unproductive elderly are sometimes abandoned or killed. Infanticide is common in a number of hunter gatherer tribes:

Another circumstance associated with infanticide is a short birth interval: i.e., an infant born within only two years of the birth of the mother’s previous child that is still nursing and being carried. It is difficult or impossible for a woman to produce enough milk for a two-year-old and also for a newborn, and to carry not just one but two children while shifting camp. For the same reason, twin births by hunter-gatherer women may result in the killing or neglect of at least one of the twins. Here is an interview with an Ache Indian named Kuchingi reported by Kim Hill and A. Magdalena Hurtado: “The one [the sibling] who followed me [in birth order] was killed. It was a short birth spacing. My mother killed him because I was small. ‘You won’t have enough milk for the older one [i.e., Kuchingi],’ she was told. ‘You must feed the older one.’ Then she killed my brother, the one who was born after me.”

On the other hand, old people are often valued more highly in the West because they function as walking information storage units:

The most important function of older people in traditional societies is one that may not have occurred to readers of this book. In a literate society the main repositories of information are written or digital sources: encyclopedias, books, magazines, maps, diaries, notes, letters, and now the Internet. If we want to ascertain some fact, we look it up in a written source or else online. But that option doesn’t exist for a pre-literate society, which must rely instead on human memories. Hence the minds of older people are the society’s encyclopedias and libraries. Time and time again in New Guinea, when I am interviewing local people and ask them some question to which they are unsure of the answer, my informants pause and say, “Let’s ask the old man [or the old woman].” Older people know the tribe’s myths and songs, who is related to whom, who did what to whom when, the names and habits and uses of hundreds of species of local plants and animals, and where to go to find food when conditions are poor. Hence caring for older people becomes a matter of life or death, just as caring for one’s hydrographic charts is a matter of life or death for modern boat captains.

In the West, much of the knowledge old people have acquired is hopelessly out of date (e.g. how to operate VHS machines etc).

I thought this was another interesting point: Diamond says the Freudian idea that we are all motivated by a subconscious sex drive is more culturally determined than we realise. For hunter gatherers, the ruling psychological obsession is with food:

Freud emphasized the sex drive and its frequent frustration. But that psychoanalytic view doesn’t apply to the Siriono Indians of Bolivia, nor to many other traditional societies, where willing sex partners are almost constantly available, but where hunger for food, and preoccupation with the food drive and its frequent frustration, are ubiquitous… The significance of sex and food is reversed between the Siriono and us Westerners: the Sirionos’ strongest anxieties are about food, they have sex virtually whenever they want, and sex compensates for food hunger, while our strongest anxieties are about sex, we have food virtually whenever we want, and eating compensates for sexual frustration.

Hunter gatherers are much more cautious than Westerners. They are surrounded by dangers and small threats like insects and scratches can easily become life threatening. Diamond says that in America he is often teased for habits of excessive caution he picked up working in New Guinea. Interestingly, “macho” behaviour is unknown:

A common Western reaction to danger that I have never, ever, encountered among experienced New Guineans is to be macho, to seek or enjoy dangerous situations, or to pretend to be unafraid and try to hide one’s own fear. Marjorie Shostak noted the lack of those same Western macho attitudes among the !Kung: “Hunts are often dangerous. The !Kung face danger courageously, but they do not seek it out or take risks for the sake of proving their courage. Actively avoiding hazardous situations is considered prudent, not cowardly or unmasculine. Young boys, moreover, are not expected to conquer their fear and act like grown men. To unnecessary risks, the !Kung say, ‘But a person could die!’”

A people after my own heart.

Other things

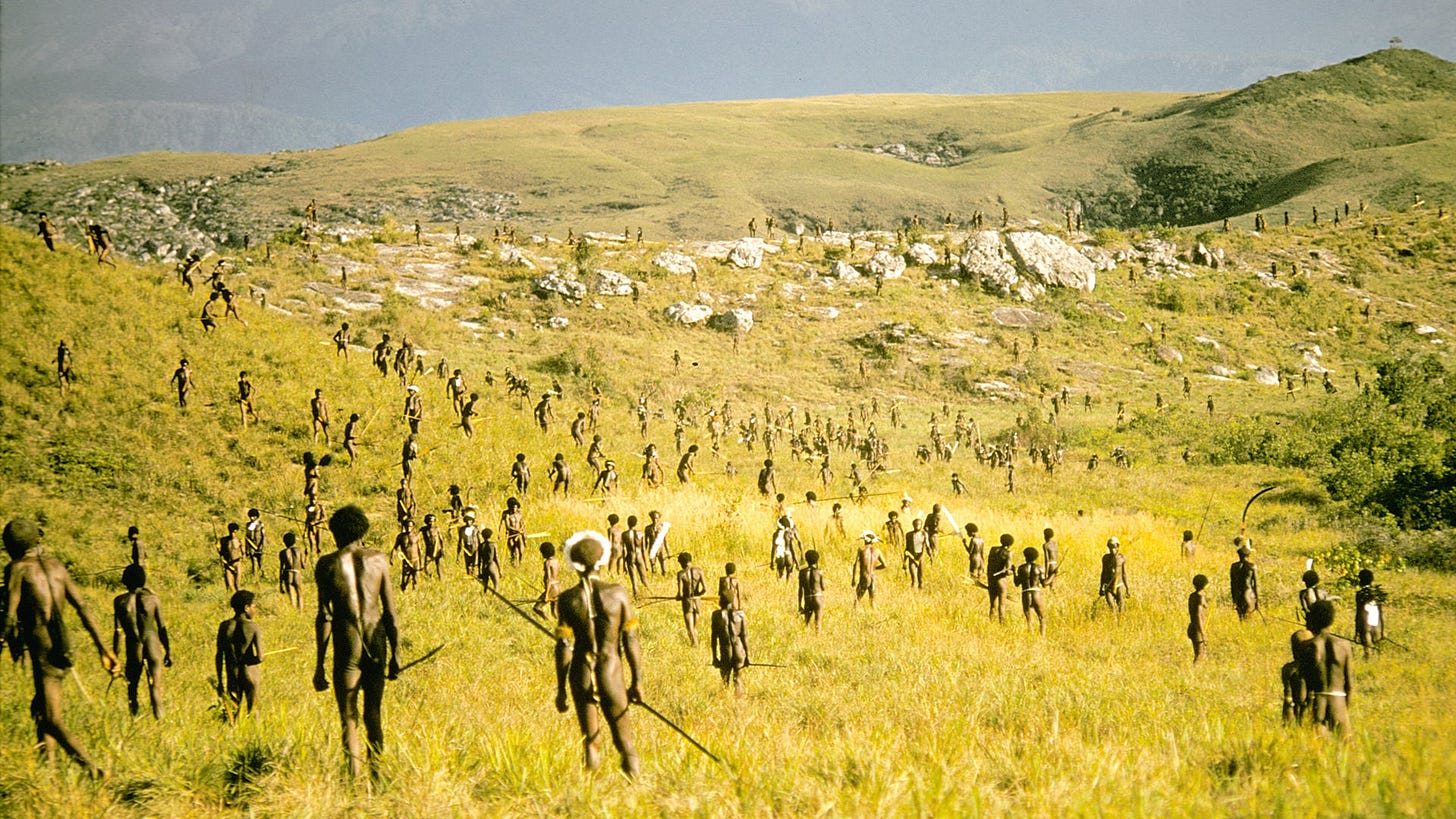

Interesting footage of tribal warfare

In The World Until Yesterday, Diamond mentions the documentary Dead Birds about tribal warfare in Papua New Guinea in the 1960s which contains rare footage of hunter gatherer conflict. I’ve only watched bits so far but it looks fascinating.

What I did on my holidays

My Times travel piece about my time in Provence is online. I had to gloss over the fact it rained a lot and the museums were often closed. It amuses me that whenever I write a travel piece and mention my girlfriend the readers below the line seem delighted and amazed to discover that I do not live, per one commenter, “alone in a garret.” Perhaps they feel the way pupils do who can’t imagine their teachers having lives outside school. Or I have “garret energy”.

At Crufts

Funny and beautifully written piece about Crufts in the LRB by Rosa Lyster in the time-honoured tradition of a snooty high-brow journalist visiting a low-brow event (think David Foster Wallace at the Illinois State Fair):

Crufts has its own shops, which include My Life as a Dog, Dog Only Nose, The Little Dog Laughed. It has products and services that you won’t find anywhere else: post-castration or post-death semen harvesting; special hair-resistant jackets, with mandarin collars offering a protective barrier against the swirling drifts of dog hair that every professional groomer has to combat; left-handed dog scissors; ‘grooming nooses’. It has its own maxims, the most frequently repeated of which is that it doesn’t matter what happens in the judging ring, you always take the best dog/bitch home with you. It has its own approved gait: that slow, bounding action handlers must perform as they lead their charges across the show ring, an uncanny, half-weightless movement, as though the person were running with weights across the bottom of a swimming pool. It has its own myths, such as the one about the Swedish breeder whose luggage was full of mineral water he had brought from home and which he used to wash his Lhasa apsos, unprepared as he was to accept the inferior results he got from the stuff that came out of the taps at the Hilton. A great innovator, one Hungarian handler called him. A pioneer.

Poem of the Week: Julian and Maddalo by Percy Bysshe Shelley

I’d never got on with Shelley much before. Ann Wroe’s book Being Shelley provided a good way in. So many of the passages she quotes seemed tantalisingly good. So I caved and bought a Selected. Sadly I think Wroe was a better advocate than Shelley perhaps deserves. I’m willing to be argued out of this opinion but I found a lot of the stuff disappointingly thin and abstract.

One amusing early warning sign was the Penguin edition of the poems I bought which is amusingly hostile about the poet whose work it is supposed to be promoting to readers. The blurb begins “Shelley’s work has been criticised for its didacticism and undisciplined emotionalism…” Not exactly a hard sell. Isabel Quigly’s introduction continues in this enjoyably scornful vein, accusing Shelley of lacking “negative capability”, not being “a pure artist”, having a “literal nature”, diffusing his “poetic energies” and exhibiting a “certain thinness in the texture of his verse”.

But there is some nevertheless some great stuff. Even Quigley eventually concedes of Shelley’s poetry that, “not all of it is bad verse”. I thought this passage from Julian and Madallo (a poetic dialogue between a Shelley-like character and a Byron-like one was stunningly good:

This ride was my delight. I love all waste

And solitary places; where we taste

The pleasure of believing what we see

Is boundless, as we wish our souls to be:

And such was this wide ocean, and this shore

More barren than its billows; and yet more

Than all, with a remember'd friend I love

To ride as then I rode; for the winds drove

The living spray along the sunny air

Into our faces; the blue heavens were bare,

Stripp'd to their depths by the awakening north;

You notice the debts to Wordsworth. The unusual deployment of “along” in “The living spray along the sunny air” is a clear borrowing from Tintern Abbey (“felt in the blood and felt along the heart”). I like the way the Wordsworthian rhythms are charged with a very un-Wordsworthian melodrama.

Oh,

How beautiful is sunset, when the glow

Of Heaven descends upon a land like thee,

Thou Paradise of exiles, Italy!

Thy mountains, seas, and vineyards, and the towers

Of cities they encircle! It was ours

To stand on thee, beholding it…

Looking upon the evening, and the flood

Which lay between the city and the shore,

Pav'd with the image of the sky.... The hoar

And aëry Alps towards the North appear'd

Through mist, an heaven-sustaining bulwark rear'd

Between the East and West; and half the sky

Was roof'd with clouds of rich emblazonry

Dark purple at the zenith, which still grew

Down the steep West into a wondrous hue

Brighter than burning gold, even to the rent

Where the swift sun yet paus'd in his descent

Among the many-folded hills: they were

Those famous Euganean hills, which bear,

As seen from Lido thro' the harbour piles,

The likeness of a clump of peakèd isles—

And then—as if the Earth and Sea had been

Dissolv'd into one lake of fire, were seen

Those mountains towering as from waves of flame

Around the vaporous sun, from which there came

The inmost purple spirit of light, and made

Their very peaks transparent.

For me this is as good as Shelley gets. But even so you can see how it gets a bit much. You can read the full poem here.

Garret energy is an admirable quality. All the romance and self-sacrifice of the artistic beau idée without actually, you know, having to live in a garret.

Too much Shelley is indeed a slog, but Ozymandias is the only poem I know by heart. Not just for its brevity, vividly imagery or the cracking twist at the end - but mainly because memorising it was a punishment set by a prefect at school. I read Other Men’s Flowers with abject shame…