Hello,

Welcome to Cultural Capital. This week I wrote my column about the end of the age of idealism. I also finally finished Thomas Mann’s great novel The Magic Mountain. I’d intended to write about it but I now realise it would probably be ridiculous to break such an extraordinary (and extraordinarily long!) book down into digestible quotes for a newsletter. So this instalment features another book I read much more quickly last week, the Australian art critic Robert Hughes’s memoir Things I Didn’t Know. Hughes is a hero of mine (to the extent that I have just bought a framed portrait of him to hang in the study of my flat). I think he was one of the very best critics of the second half of the twentieth century and a superb writer. His burly, demotic, rather lordly prose style has been aptly characterised as “Augustan jive”. I am constantly re-reading the essays collected in his book Nothing if Nor Critical. His brilliant TV series about modern art, The Shock of the New is one of the greatest documentaries ever made and certainly the best-written (in episode one an early biplane is a “buzzing wooden dragonfly”).

Things I Didn’t Know

The memoir follows Hughes from his childhood and adolescence at a strict Jesuit school in 1950s Sydney and ends with him flying off to America to work at Time magazine where he made his name. It has its flaws: you learn too much about his family history and there are endless digressions about how evil his ex-wife is. But I always love reading about how people came of age intellectually. Hughes was exceptionally (perhaps insufferably) precocious. I think he is correct that the literary education he acquired in his teens has now been rendered impossible by television:

I could recite the whole of Shelley’s “Adonais” without prompting from a book, and I may have been the only sixteen-year-old in Sydney who knew The Waste Land word-perfect and by heart—if anyone didn’t believe it, moreover, I could and sometimes did punish him by beginning with “April is the cruelest month” and keeping on until the impious wretch begged for mercy. This usually happened when he had begun to recover from his surprise, somewhere around “What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow / Out of this stony rubbish?”—a line that brought to mind parts of the Australian bush. I also memorized long stretches of Shakespeare and short ones of Marlowe: all of Macbeth and Julius Caesar—for in school play productions I had played the parts of both Brutus and the gloomy, guilt-ridden Scot—and even bits of Doctor Faustus and Tamburlaine, especially that sublime and terrifying soliloquy that precedes Faustus’ descent into eternal Hell—“See, see, where Christ’s blood streams in the firmament!” I am certain that none of this stuff would have stayed with me if television had existed in Australia then. There is no doubt in my mind that in cultural matters, at least among impressionable teenagers, bad money does indeed drive out good. Hang me for a filthy elitist, but it’s true. Which is why I cannot feel much more than a regretful contempt for those goggling children who spend their evenings screeching at American Idol.

It is remarkable to think that when Hughes was growing up in Australia not only was there very little art to see but there weren’t even many good reproductions to look at either. That scarcity made those thrilling teenage moments of cultural discovery even more electric.

Father O’Connell [a science teacher at Hughes’s Jesuit school], as it would turn out, changed my life in other ways. He made regular trips to Europe in order to advise the papal observatory at Castel Gandolfo, outside Rome. On these trips, being keen on art, he would collect postcard reproductions of paintings that struck his fancy. Though Riverview offered its pupils no art instruction of any kind, Father O’Connell would from time to time pin up some of these pictures, with brief comments that he would type himself, on one of the bulletin boards outside the school refectory. One of these postcards—I forget the year in which he pinned it up—was of a modern painting: de Chirico’s famous image, completely new and unfamiliar to me then, of a girl bowling her hoop along an empty piazza, Mystery and Melancholy of a Street, 1914. I was completely transfixed by it; I had never seen anything so strange and inexplicably moving.

And this bit was very good on how we have to discover great art for ourselves and that we are unlikely to “get” absolutely all of it. I always think the most reliable sign of a pseud is someone who claims they like every famous artist and every celebrated author. Everyone who really likes art and literature knows that’s just not possible.

. . . at this stage of my life that I began to get some firsthand idea of what great sculpture could be. It may seem ridiculous that this awareness took so long to dawn. But it only comes about from discoveries you feel you have made for yourself. Sometimes a great work of art can be so monotonously praised that out of sheer obstinacy, not to say perversity, you resist it. It can even verge on the comic, as my sight of Michelangelo’s Pietà at the World’s Fair did. It doesn’t matter how often, or insistently, you are told that an artist is great: unless you experience it for yourself the term will never mean anything to you, it will just be someone else’s clanking superlative. Your only course is to come back later. And even then the promised experience may not arrive. The arch example, for me, would be the work of Paul Cézanne, whom everyone considers to be the absolute god of modern painting, the initiator and forefather. The fact that, apart from critics and art historians, so many artists whose work I admire have thought so makes me feel, with respect to Cézanne, rather an outsider. For, to be honest about it, Cézanne’s work (except for some of his water-colors and certain landscapes and still lifes) has never awoken any real rapture in me, and his big awkward figure compositions of nudes, which others consider the summit of his achievement and do not hesitate to compare to the work of Michelangelo, Poussin, and any number of other masters, leave me quite cold and unconvinced. Not all “masterpieces” are necessarily masterpieces for everyone, and if they were, taste would remain static down the centuries, which fortunately it does not.

Other Things

How to Fix the New Statesman

Months after Jason Cowley’s resignation, the New Statesman still doesn’t have an editor. I am a great fan of the writer James O’Malley who has republished his long and interesting piece about how he would fix the magazine, but this time without the paywall. He argues that the New Statesman could significantly grow its subscriber base if it stopped publishing “snooty essays about capitalism written by people who probably boast that they don’t own a TV” and embraced its role as the in-house magazine of the Labour Party. It should try to appeal to a more “middlebrow” audience:

To use myself as an example – and I realise that I may not be particularly representative – a lot of what the NS publishes, particularly in its arts and books coverage, as well as the long and torturous essays that always conclude that the answer is capitalism is bad, just leave me completely cold.

And given that I’m Masters Degree educated and the sort of person who likes reading long essays about politics, if I’m not interested, what does that say about the size of the potential audience for this sort of content?

So it strikes me that there’s a potentially much larger audience for NS content if it would just aim to be a touch more accessible.

In fact, the potential market opportunity of going ever-so-slightly-lower-brow can be seen from miles away. Look at the huge success of Alistair Campbell and Rory Stewart, The News Agents, or even YouTubers like Johnny Harris and Wendover Productions. Similarly, the New European, which has slightly more tabloid sensibilities, has nearly caught up to the NS in terms of circulation, despite the NS’s century long head start.

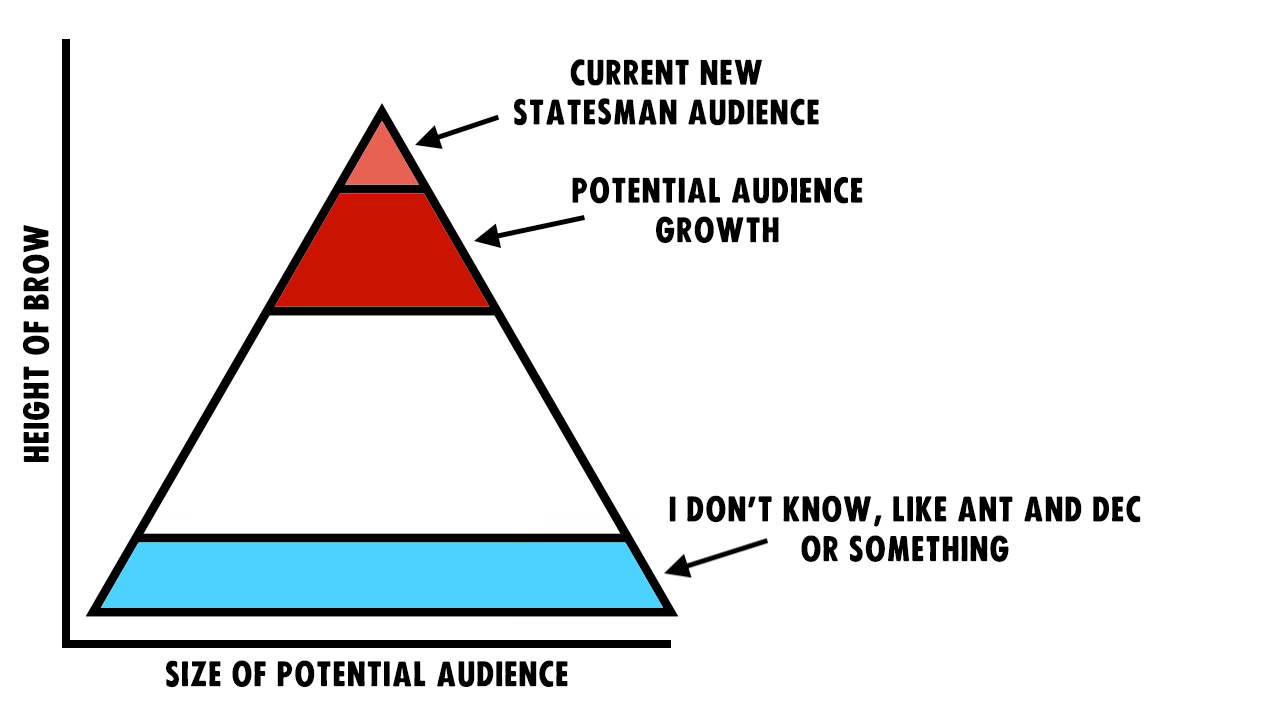

He summarises his proposed strategy in this graph:

Obviously this is all painful reading to me. A lot of what O’Malley thinks is wrong about the New Statesman — its pessimism about technology, its arts and books section, its snooty essays, John Gray — is what I like about it. But, as we are constantly reminded, it is good to expose ourselves to points of view we disagree with and he makes his case well.

Euphoria, Suffer, Ferret

The words “euphoria”, “suffer” and “ferret” all derive from the same Proto-Indo-European verb for “to carry”.

Obligatory Robert Hughes Essay

This one is on Cezanne. Interesting that he writes so well about an artist he claims not to “get” (see above). Here he is on Cezanne’s Large Bathers:

. . . one sees the characteristics that have always rendered these peculiar arcadian scenes difficult to love even as they compel admiration and even a certain awe. This group of 14 stock nudes gathered around what must have been a picnic basket is as resolutely antisensuous as an assembly of naked women could possibly be. Some of them look like seals stranded on rocks. Others are lumpish giantesses. None were painted from actual models because, as his friend the painter Emile Bernard recalled, “he was the slave of an extreme sense of decorum, and…this slavery had two causes: the one, that he didn’t trust himself with women; the other, that he had religious scruples and a genuine feeling that such things could not be done in a small provincial town without provoking scandal.” Instead, he recycled his old art-school drawings, a process which must have contributed to the strangely abstract look of the figures.

Cezanne’s sublimation produces not flesh but a kind of architecture. Yet this architecture is incontrovertible. Its scale is increased by the overarching trees, which supply a Gothic vault, and by the high, cloud-laden sky.

Peter Hitchens Podcast

A curious insight into the worldview of Peter Hitchens on his new podcast. I am very far from agreeing with him on every issue but I find him interesting for his genuinely independent and internally coherent worldview. Prompted to nominate the country that best fulfils his political ideals, Hitchens suggests France. He says that he is an admirer of “French basic ruthlessness” and considers himself a “Gaullist”.

Repatrimonialisation

Francis Fukuyama compellingly argues that Trump is returning America to a pre-modern “patrimonial” state, i.e. one based on personal relationships rather than on the impersonal responsibilities of bureaucrats and legislators. He says this is the “characteristic” form of corruption facing backsliding twenty-first century democracies.

One of the big themes of my two Political Order volumes was the great difficulty of creating an impersonal modern state, in which your status depended on citizenship and not on your personal relationship with the ruler. A modern economy is only possible under these circumstances as well, as the state undertakes to protect property rights and adjudicates transactions without regard to the identity of the rights-holder.

The problem with state modernity is that it is unstable. Human beings are by nature social creatures, but their sociability takes the form in the first instance of favoritism to friends and family. This leads to the phenomenon of “repatrimonialization,” a long word signifying the retreat of a modern impersonal state back into patrimonialism. This is a phenomenon that has plagued many earlier societies, like Tang Dynasty China, or the 17th century Ottoman Empire, or France under the Old Regime. In each case, an emergent modern state was captured by powerful elites close to the ruler. In France, for example, the king sold rent-seeking privileges like tax collection to the highest bidder.

Sally Rooney on Snooker

Why can computers beat human beings at chess, but not (yet) at snooker? This time there’s an answer. In computational terms, snooker is simply a lot more difficult than chess. An ordinary phone or laptop has more than enough computing power to find an optimal chess move in almost any given position within a few seconds or less. But for a computer to play snooker, even with a perfectly accurate robotic arm, it would first have to calculate how exactly to strike the cue ball. And to do that, it would need access to a model or engine that could simulate the real-world physics of the table and balls and predict precisely the result of any given shot. That would take quite a bit more computing power than your phone can provide.

Pool and snooker simulations do exist—various video games depend on them, including the now-defunct World Snooker Championship series—but the underlying physics engines rely on simplified models. When a snooker ball hits a cushion, for instance, how does the simulation know what’s going to happen next? Well, it doesn’t. Even complex models of the ball–cushion interaction have to assume that the collision between ball and cushion is instantaneous, which it isn’t, and that the cushion won’t compress significantly on impact, which, as any snooker fan knows, it can. And the best existing formulas are still too complex to be useful for a video game simulation. For the moment, any computer that wants to play snooker has to rely on a more simplistic model with less accurate results.

From a mathematical perspective, then, snooker presents a much harder problem than chess, involving more difficult calculations and many more variables. But that just brings us back to our first question: If the physics of snooker is so complicated, why should human beings be able to play it better than computers can? And relatedly: How is it possible for a snooker player to predict the outcomes of complex interactions in physics, with millimeter-level precision—without appearing to perform any calculations at all?

Trump Diary

The political scientist Adam Przeworskiis is keeping a weekly diary of life under the Trump administration. As he explains:

I decided to keep a record of my thoughts as events transpire, a diary. I have read several reactions by Germans to the rise of Nazism and I was struck by their difficulty to understand where the daily events they lived through could or would lead. In retrospect, we will know, analyze, and make sense. In retrospect everything will have been determined. We may conclude, as did Amos Alon (The Pity of It All) that what did transpire was not inevitable, that history may have taken a different course. But prospectively we can only fear or hope and we do not know which. I have dark premonitions but this is all I have. So my purpose is only to inform the future retrospect by providing a record of my gut reactions to the daily events, as they happen.

Here is a link to the most recent one.

Poem of the Week: ‘And You Know’ by John Ashbery

John Ashbery is one of my favourite poets. I have a weakness for the lovely but meaningless which is Ashbery’s speciality (I mean that as a compliment). ‘And You Know’ is from his first collection Some Trees which is in my view one of the essential books you have to own if you like poetry. It is impossible to say what this strange and surreal poem is about but I find it beautiful and moving nonetheless. If pressed I would suggest that it is set in a girl’s school where an old schoolmaster is passing on his wisdom to his pupils:

The girls, protected by gold wire from the gaze

Of the onrushing students, live in an atmosphere of vacuum

In the old schoolhouse covered with nasturtiums.

At night, comets, shooting stars, twirling planets,

Suns, bits of illuminated pumice, and spooks hang over the old place;

Wisdom is beautiful but it is also sad because it contains life with all its disappointments and wearying experiences. And so the world of the schoolmaster is lovely but also ancient and decaying in a way that might be oppressive to some of his pupils. At the end of the poem the girls seem to have left the schoolmaster and we sense that without their presence that he has lost their rejuvenating energy:

And so they have left us feeling cross and tired

They never cared for school anyway.

And they have left us with the things pinned on the bulletin board,

And the night the endless muggy night that is invading our school.

The poem is somehow full of an atmosphere of nostalgia and romance and being young and being at school. In Ashbery, atmosphere and feeling come first and sense comes second. He is wonderful at deploying colour:

And we shall visit these places, you and I, and other places,

Including heavenly Naples, queen of the sea, where I shall be king and you will be queen,

And all the places around Naples.

So the good old teacher is right, to stop with his finger on Naples, gazing out into the mild December afternoon

As his star pupil enters the classroom in that elaborate black and yellow creation.

He is thinking of her flounces, and is caught in them as if they were made of iron, they will crush him to death!

“That black and yellow creation”! Like a bee or a wasp? Some poets like JH Prynne give the impression of thinking that being incomprehensible is a sign of their importance and profundity. Ashbery at his best is always ironising his own meaninglessness. He refuses to be serious about not making sense. His best poems have an atmosphere of irresistible charm and whimsy. To me the few weaknesses in ‘And You Know’ are the moments where the poem seems to be using the excuse of meaninglessness to sound impressive just for the sake of it: e.g. “I teach reading and writing and flaming arithmetic” (flaming is a bit much for me). Anyway, it’s fantastic.

Another interesting read, thank you. Also, for the Shock of the New recommendation. Superb series I'm now in the midst of.

"Look at the huge success of Alistair Campbell and Rory Stewart, The News Agents..." As a happy subscriber to the New Statesman under Jason Cowley's editorship, I dread the possibility of a new editor who wants the magazine to align with The News Agents, let alone the useful idiots Campbell and Stewart, particularly following their poorly judged (to put it extremely mildly) interview with Abu Mohammed al-Jolani/Ahmed al-Sharaa. And I don't want the magazine to be a part of "the Labour family", whatever that is; it sounds like a transformation into an organ of propaganda. The New Statesman has been so good for a while; it could so easily be ruined.

Fatal Shore is a superb book. I love this remark about Hughes from Clive James:

"Hughes is the Bastard from the Bush dressed up as the Wandering Scholar. Thousands of bright young Aussies will want to be him, in the same way that thousands of slightly less bright Aussies want to be the cricketer Shane Warne."

What Sydney University must have been like in that era - not only Hughes and James, but also Germaine Greer, Les Murray, Bruce Beresford, all churning round, full of enthusiasm and ideas.